The Tissues

Chapter 6

Anatomy of flowering plants

Both plants and animals have structural similarities and differences in their outward appearance that can be easily viewed. Furthermore, the interior structure of living creatures shares certain characteristics. The internal structure and organization of higher plants are discussed in this chapter. Anatomy is the study of a plant's interior structure. Cells are the basic unit of plants, and cells are organized into tissues, which are then organized into organs. Different organs of a plant have different internal structures. Monocots and dicots are considered to be physically distinct within angiosperms. Internal structures also exhibit environmental adaptations.

Tissues

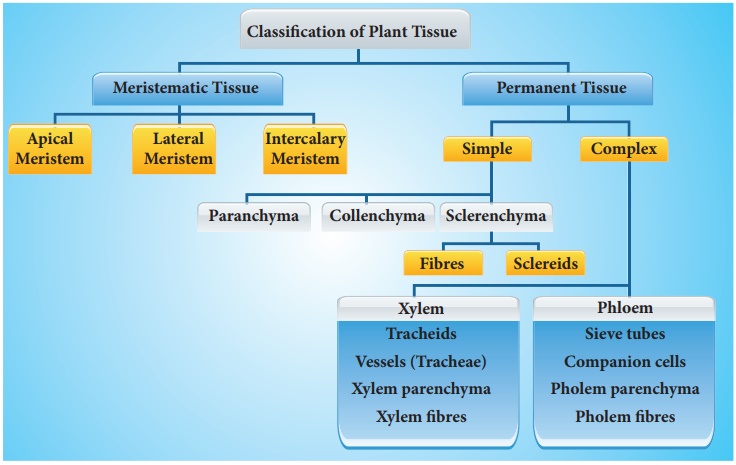

A tissue is a collection of cells that share the same origin and typically execute the same function. Different types of tissues make up a plant. Tissues are divided into two categories: meristematic and permanent tissues, depending on whether or not the cells forming them are capable of dividing.

A. Meristematic Tissues

Meristematic tissue is a type of plant tissue that can divide continuously throughout its existence. Plant growth is generally restricted to meristems, which are specialized regions of active cell division. Meristems come in several forms in plants. Primary meristems include apical and intercalary meristems, which arise early in a plant's life and contribute to the production of the primary plant body.

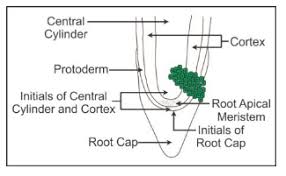

Apical meristems are meristems that form at the terminals of roots and shoots and create primary tissues. The root apical meristem is found at the root's tip, while the shoot apical meristem is found at the far end of the stem axis. The axillary bud is formed by cells left over from the shoot apical meristem after the production of leaves and stem elongation. These buds can develop a branch or a flower and can be found in the axils of leaves.

Intercalary meristem is a type of meristem that arises between mature tissues. They are present in grasses and restore sections of the plant that have been eaten by grazing herbivores. They are found in the leaves and internodes. These contribute to the internode's lengthening. It is also present in monocots, and pine trees. It contributes to the plant's height.

The secondary or lateral meristem is found in the mature portions of roots and shoots of many plants, especially those that generate woody axes and develop later than the primary meristem. They are meristems that are cylindrical. Lateral meristems include the fascicular vascular cambium, interfascicular cambium, and cork-cambium. The secondary tissues are produced by these cells. Following cell division in both primary and secondary meristems, newly produced cells become architecturally and functionally specialized, and their ability to divide is lost. Permanent or mature cells are the cells that make up the permanent tissues. Specific parts of the apical meristem produce dermal tissues, ground tissues, and vascular tissues during the creation of the main plant body.

B. Permanent Tissues:

Permanent tissues are made up of mature cells that have lost their ability to divide and have taken on a permanent shape, size, and function as a result of meristematic tissue development and differentiation. These tissues' cells can be alive or dead, thin-walled or thick-walled. Permanent tissue cells do not usually divide any further. They are divided into simple tissues and complex tissues.

Simple tissues

are permanent tissues with all cells having the same structure and function.Only one sort of cell makes up a basic tissue. Plants have parenchyma, collenchyma, and sclerenchyma as simple tissues. The parenchyma cells form a majority of the living cells in the plant. The parenchyma's cells are usually isodiametric. They come in a variety of shapes, including spherical, oval, round, polygonal, and elongated. Their cellulose-based walls are quite thin. They might be tightly packed or with minor intercellular gaps. Photosynthesis, storage, and secretion are all processes performed by the parenchyma. In most dicotyledonous plants, the collenchyma is found in layers beneath the epidermis. It can be found as a single layer or in patches. It is made up of cells that have thickened at the corners due to cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin deposition.Collenchymatous cells can be oval, round, or polygonal, and chloroplasts are common. When chloroplasts are present, these cells digest food. There are no intercellular spaces. They offer mechanical support to the plant's growth portions, such as the young stem and leaf petiole. Long, narrow cells with thick, lignified cell walls and a few or many pits make up sclerenchyma. They are frequently devoid of protoplasts and lifeless. Sclerenchyma can be classified as fibers or sclereids based on differentforms, structures, origins, and development. Fibers are thick-walled, elongated, cells that can be found in groups throughout the plant. Sclereids are dead cells that are spherical, oval, or cylindrical in shape and have very thin cavities (lumen).These are often found in nut fruit walls, fruit pulp such as guava, pear, and sapota, legume seed coats, and tea leaves. Organs are supported mechanically by sclerenchyma.

Complex tissues

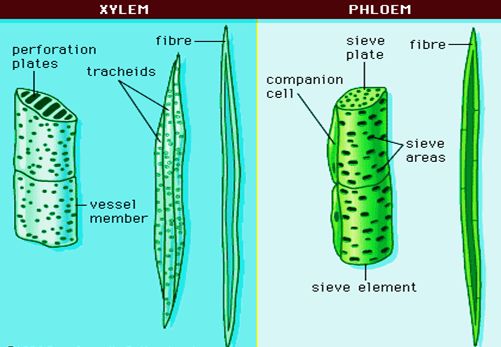

are permanent tissues that contain a variety of cell types.They are made up of multiple cell types that work together as a unit. Plants have complex tissues called xylem and phloem. From the roots to the stem and leaves, the xylem serves as a conduit for water and minerals. It also gives the plant parts mechanical strength. Tracheids, vessels, xylem fibres, and xylem parenchyma are the four types of elements that make up the xylem. The xylem of gymnosperms is devoid of vessels. Tracheids are long, tube-like cells with lignified walls and tapering ends. These have no protoplasm and are dead. The inner layers of the cell walls feature different types of thickenings. Tracheids and vessels are the principal water transportation elements in blooming plants.A vessel is a long cylindrical tube-like structure composed of multiple vessel parts, each with lignified walls and a big central chamber. The vascular cells are also protoplasm-free. Members of the vessel are linked through perforations in their common walls. Angiosperms are characterized by the presence of vessels. The walls of xylem fibers are thicker and the central lumens are destroyed. These can be septate or aseptate in nature. Xylem parenchyma cells are live, thin-walled cells with cellulose-based cell walls. They store food items such as starch or fat, as well as other compounds such as tannins. The ray parenchymatous cells are responsible for water radial conduction.

Protoxylem and metaxylem are the two forms of primary xylem. Protoxylem refers to the first created primary xylem elements, while metaxylem refers to the later formed primary xylem components. The protoxylem is located at the organ's center (pith), while the metaxylem is located near the organ's perimeter. Endarch is the name for this sort of primary xylem. Protoxylem is found on the periphery of roots, while metaxylem is found in the centre. Exarch is the name for this type of primary xylem configuration. Food supplies are transported via phloem from leaves to other sections of the plant. Sieve tube elements, companion cells, phloem parenchyma, and phloem fibres make up phloem in angiosperms. Albuminous cells and sieve cells are found in Gymnosperms. Sieve tubes and companion cells aren't present.

Sieve tube elements are similar to companion cells in that they are long, tube-like structures that are aligned longitudinally. The sieve plates are formed by perforating their end walls in a sieve-like pattern. A developed sieve element has a big vacuole and peripheral cytoplasm but no nucleus. The nucleus of companion cells controls the actions of sieve tubes. Companion cells are specialized parenchymatous cells that are intimately linked to sieve tube elements. Between their common longitudinal walls, pit fields connect the sieve tube elements and companion cells. The partner cells aid in maintaining the sieve tubes' pressure gradient. Elongated, tapered cylindrical cells with rich cytoplasm and nucleus make up phloem parenchyma.The cellulose cell wall has pores through which plasmodesmata connections between cells can be made. Food and other compounds like as resins, latex, and mucilage are stored in the phloem parenchyma. The majority of monocotyledons lack phloem parenchyma. Sclerenchymatous cells make up phloem fibers. The primary phloem is devoid of them, whereas the secondary phloem has them. These are long and unbranched, with sharp, needle-like apices. Phloem fibers have a very thick cell wall. These fibers lose their protoplasm and die as they mature. Protophloem is the first created primary phloem, which has tiny sieve tubes, and metaphloem is the second formed primary phloem, which has larger sieve tubes.

The Tissue System

The Tissue System

There are three types of tissue systems based on their structure and location.

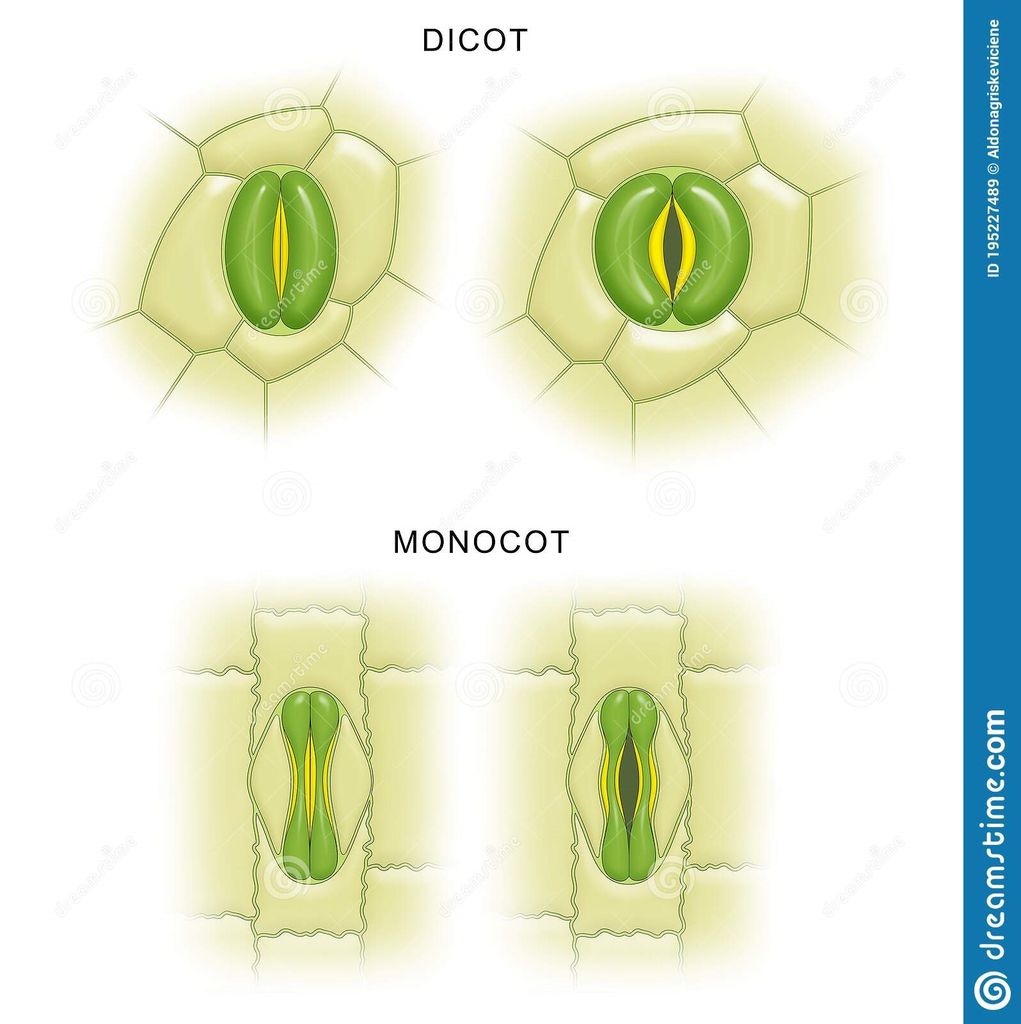

A. The epidermal tissue system

Epidermal cells, stomata, and epidermal appendages like trichomes and hairs make up the epidermal tissue system, which covers the entire plant body. The epidermis is the major plant body's outermost layer. It is made up of a continuous layer of elongated, compactly packed cells. The epidermis is normally one layer thick. Epidermal cells are parenchymatous, with a big vacuole and a little quantity of cytoplasm along the cell wall. The cuticle, a waxy thick covering on the outside of the epidermis that resists water loss, is commonly present. The roots have no cuticle. The epidermis of leaves has features called stomata. The process of transpiration and gas exchange is regulated by stomata.Guard cells enclose the stomatal pore in each stoma, which are two bean-shaped cells. The guard cells in grasses are formed like a dumbbell. Guard cells have thin outer walls that face away from the stomatal pore and robust interior walls that face the stomatal pore. Guard cells have chloroplasts and control stomata opening and closing. A few epidermal cells near the guard cells can become specialized in shape and size, and these cells are known as subsidiary cells. The Stomatal apparatus is made up of the stomatal orifice, guard cells, and surrounding subsidiary cells. Hairs are found on the epidermis cells.Root hairs are unicellular epidermal elongations that assist absorb water and minerals from the soil. Trichomes are epidermal hairs that grow on the stem. In the shoot system, trichomes are frequently multicellular. They might be soft or stiff, branching or unbranched. They could even be hidden. The trichomes aid in the prevention of water loss by transpiration.

B. The ground tissue system

It is also called the foundational tissue system.The ground tissue is made up of all tissues save the epidermis and vascular bundles. Simple tissues such as parenchyma, collenchyma, and sclerenchyma make up this layer. In the cortex, pericycle, pith, and medullary rays, as well as the primary stems and roots, parenchymatous cells are commonly seen. The mesophyll is the ground tissue in leaves that is made up of thin-walled chloroplast-containing cells. Ground tissue includes parenchyma (photosynthesis in the leaves and storage in the roots), collenchyma (shoot support in areas of active growth), and sclerenchyma (shoot support in areas where growth has ceased) and is the site of photosynthesis, provides a supporting matrix for the vascular tissue, provides structural support for the stem, and helps to store water and sugars, depending on the cell type and location in the plant.

C. The vascular tissue system:

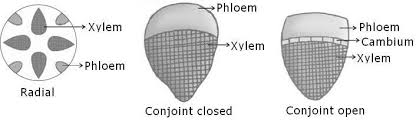

Also called conducting tissue system. The vascular system is made up of two complicated tissues: phloem and xylem. Vascular bundles are made up of the xylem and phloem. Between the phloem and xylem in dicotyledonous stems, there is cambium. Because of the existence of cambium, such vascular bundles have the ability to produce secondary xylem and phloem tissues, and are hence referred to as open vascular bundles. The cambium is absent from the vascular bundles of monocotyledons. As a result, they are referred to as closed since they do not generate additional tissues. Radial arrangement occurs when xylem and phloem within a vascular bundle are placed in an alternative fashion along distinct radii, as in roots.The xylem and phloem are located along the same radius of vascular bundles in conjoint type vascular bundles. In stems and leaves, vascular bundles are common. Phloem is usually exclusively seen on the outer side of the xylem in conjoint vascular bundles.

Anatomy of Dicotyledonous and Monocotyledonous Plants

Anatomy of dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants

Transverse sections of the mature zones of roots, stems, and leaves are useful for better understanding the tissue organization of these organs.

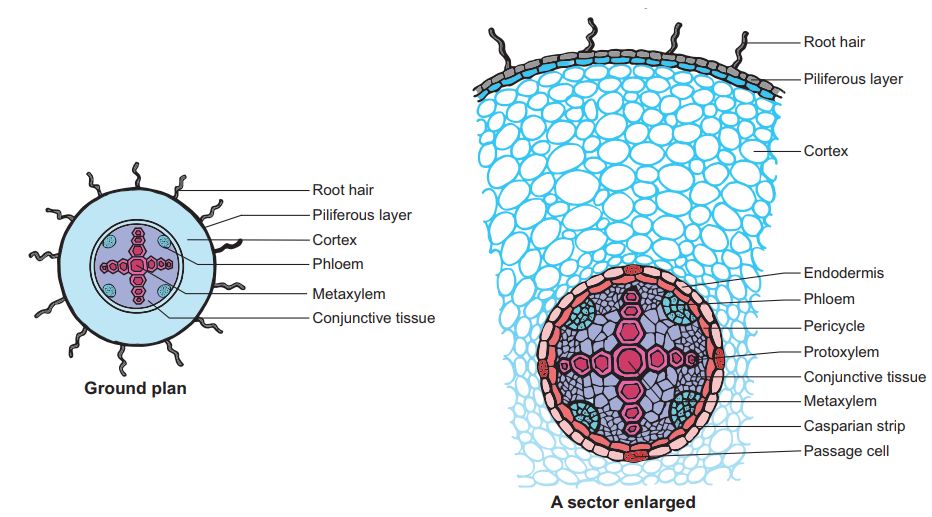

A.Dicotyledonous Root: The interior tissue organization is as follows:

1. Epiblema is the outermost layer in the interior tissue architecture. Epiblema cells emerge as unicellular root hairs on many occasions.

2. The cortex is made up of many layers of parenchymal cells with thin walls and intercellular gaps.

3. Endodermis is the cortex's deepest layer. There are no intercellular gaps in the single layer of barrel-shaped cells.

4. Water-impermeable waxy substance suberin is deposited in the form of Casparian strips on the tangential as well as radial walls of endodermal cells.

5. A few layers of thick-walled parenchymatous cells called pericycle are found next to the endodermis. During secondary growth, these cells initiate the formation of lateral roots and vascular cambium.

6. The pith is small and undetectable.

7. Conjuctive tissue is made up of parenchymatous cells that reside between the xylem and the phloem. Two to four xylem and phloem patches are typical. A cambium ring forms later between the xylem and the phloem.

8. The stele is made up of all tissues on the inner side of the endodermis, such as the pericycle, vascular bundles, and pith.

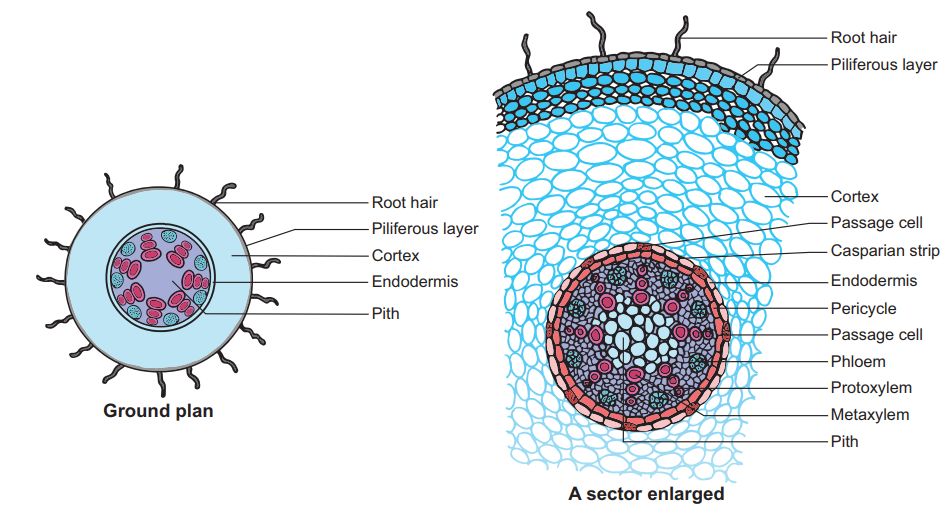

B. Monocotyledonous Root: In many ways, the monocot root's anatomy is identical to that of the dicot root.

1. Epidermis, cortex, endodermis, pericycle, vascular bundles, and pith are all present.

2. Unlike the dicot root, which has fewer xylem bundles, the monocot root frequently has more than six (polyarch) xylem bundles.

3. The pith is thick and developed.

4. There is no secondary development in monocotyledonous roots.

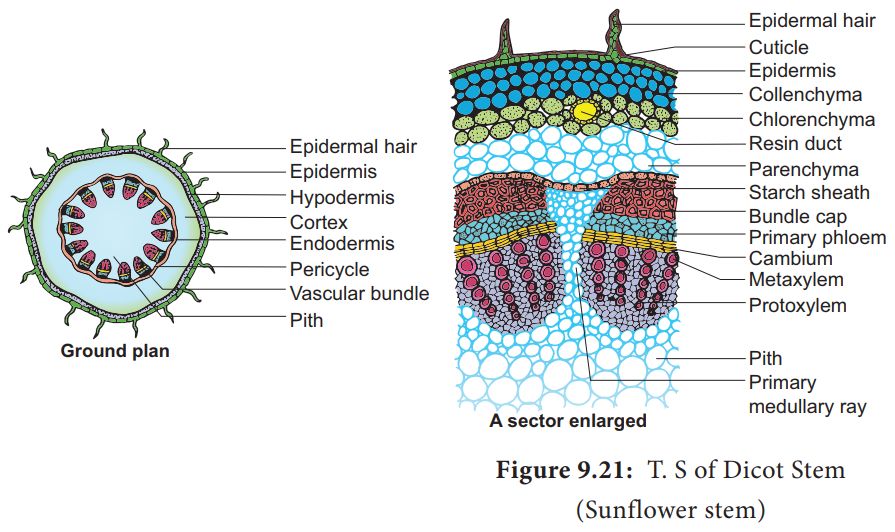

C. Dicotyledonous Stem:

1. The epidermis is the stem's outermost protective covering, as shown in this transverse section of a typical immature dicotyledonous stem.

2. It may have trichomes and a few stomata and is covered in a thin layer of cuticle.

3. The cortex is made up of cells organized in many layers between the epidermis and the pericycle. It is divided into three zones.

4. Just below the epidermis, the outer hypodermis consists of a few layers of collenchymatous cells that offer mechanical support to the embryonic stem.

5. The cortical layers underneath the hypodermis are made up of spherical parenchymatous cells with visible intercellular gaps.

6. The endodermis is the deepest layer andbecause the endodermis cells are densely packed with starch grains, the layer is also known as the starch sheath.

7. Pericycle appears as semi-lunar patches of sclerenchyma on the inner side of the endodermis and above the phloem.

8. Medullary rays are a few layers of radially arranged parenchymatous cells that lie between the vascular bundles.

9. A ring of vascular bundles surrounds the stem of a dicot. Each vascular bundle is joined, open, and has a protoxylem at the end.

10. The pith is made up of a large number of spherical, parenchymatous cells with extensive intercellular gaps that occupy the middle region of the stem.

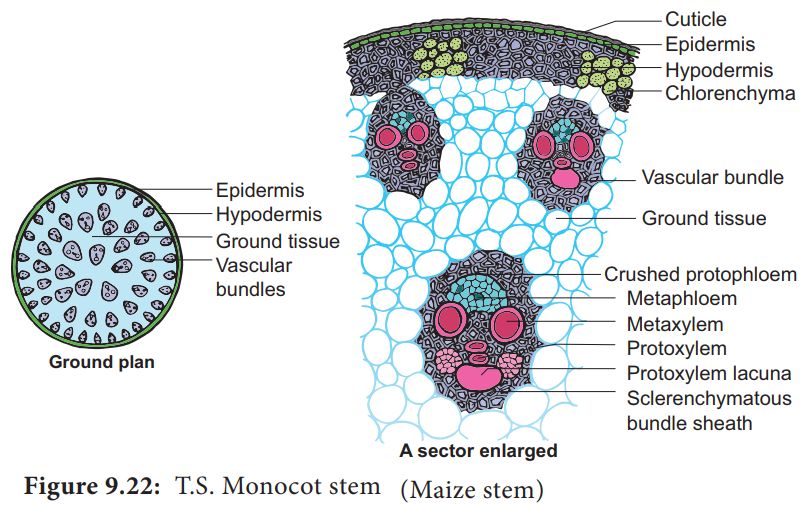

D. Monocotyledonous Stem:

1.A sclerenchymatous hypodermis, numerous distributed vascular bundles, each enclosed by a sclerenchymatous bundle sheath, and a broad, prominent parenchymatous ground tissue characterize the monocot stem.

2. The vascular bundles are joined and closed together. Vascular bundles at the periphery are typically smaller than those in the center.

3. The phloem parenchyma is missing, and there are water-filled holes inside the vascular bundles.

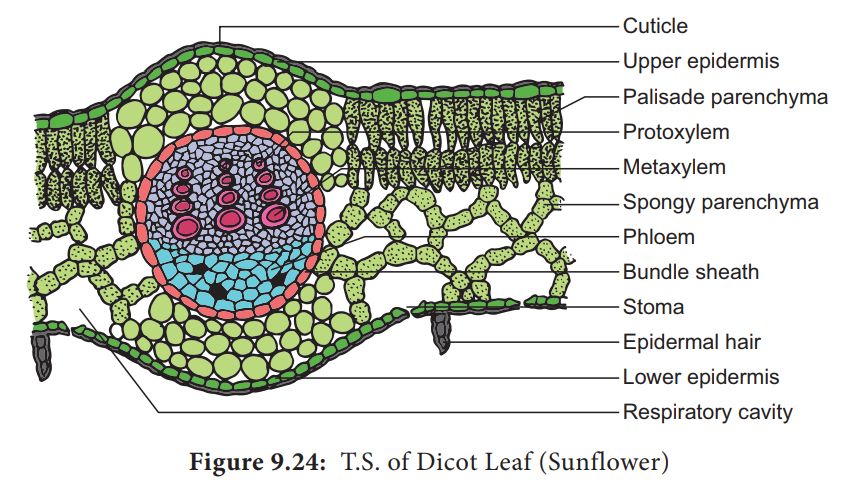

E. Dicotyledonous Leaf:

They are also called Dorsiventral Leaves.

1. The epidermis, mesophyll, and vascular system are visible in a vertical piece of a dorsiventral leaf through the lamina.

2. The epidermis of the leaf has a prominent cuticle that covers both the upper (adaxial epidermis) and bottom (abaxial epidermis).

3. In general, the abaxial epidermis has more stomata than the adaxial epidermis.

4. Stomata may even be absent in the upper epidermis. The mesophyll is the tissue that lies between the top and lower epidermis.

5. The mesophyll is made up of parenchyma, which contains chloroplasts and performs photosynthesis.

6. The palisade parenchyma and the spongy parenchyma are two types of cells. The elongated cells that make up the adaxial palisade hepatocytes are organized vertically and parallel to each other.

7. The spongy parenchyma, which is oval or spherical and loosely organized, is found underneath the palisade cells and reaches the lower epidermis. Between these cells are various huge gaps and air cavities.

8. Vascular bundles can be found in the veins and midrib of the vascular system. The size of the vascular bundles is determined by the vein size.

9. The veins in the dicot leaves' reticulate venation vary in thickness. A layer of thick-walled bundle sheath cells surrounds the vascular bundles.

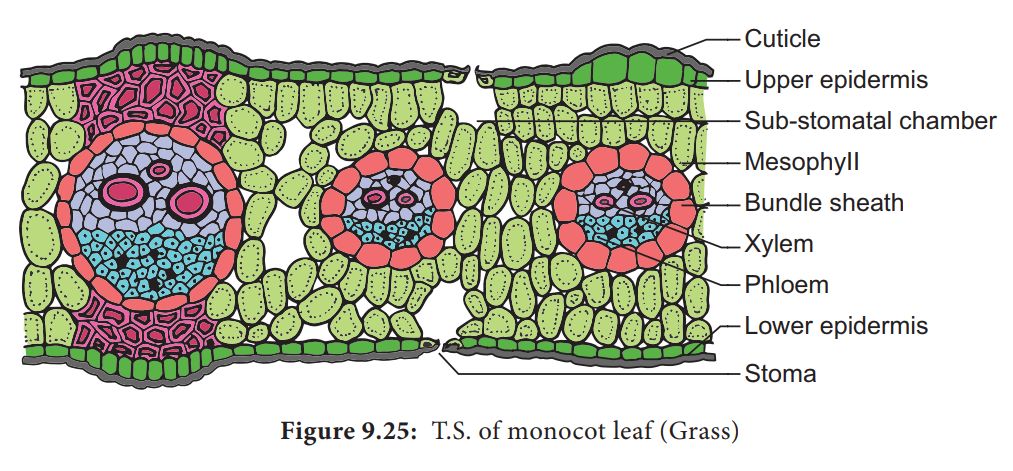

F. Monocot Leaf:

They are also known as Isobilateral Leaves.In many ways, the anatomy of the isobilateral leaf is identical to that of the dorsiventral leaf. It demonstrates the following distinguishing characteristics.

1. Stomata are present on both epidermal surfaces in an isobilateral leaf, and the mesophyll is not divided into palisade and spongy parenchyma.

2. Certain adaxial epidermal cells along veins in grasses transform into huge, empty, colorless cells called Bulliform cells.

3. The leaf surface is exposed when the bulliform cells in the leaves have absorbed water and are turgid. They curl the leaves inwards to reduce water loss when they are flaccid due to water stress.

4. In vertical sections of monocot leaves, the parallel venation is represented in the near comparable diameters of vascular bundles.

Secondary Growth

Secondary Growth

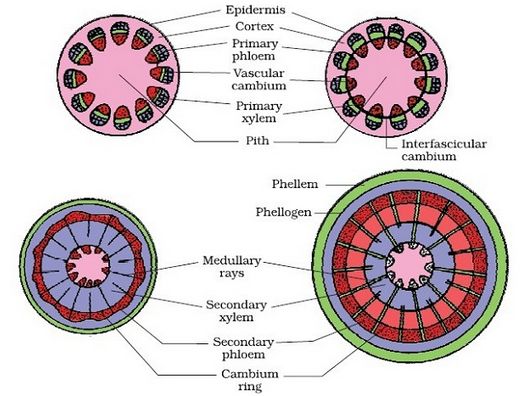

Primary growth refers to the lengthening of roots and stems with the help of the apical meristem. Most dicotyledonous plants expand in girth in addition to main growth. This is referred to as secondary growth. The two lateral meristems, vascular cambium and cork cambium, are engaged in secondary growth.

A. Vascular Cambium:

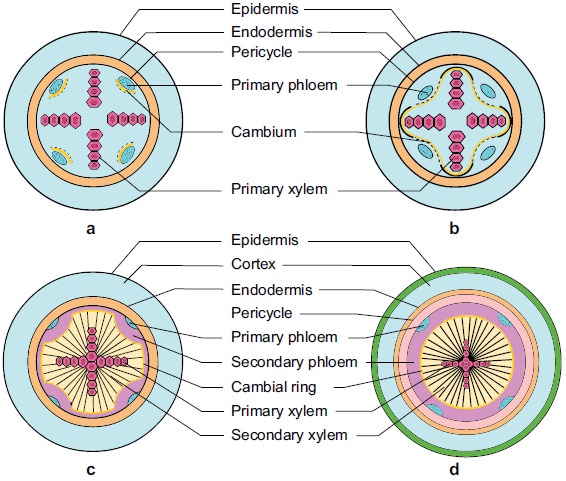

Vascular cambium is the meristematic layer responsible for cutting off vascular tissues – xylem and phloem. It appears in patches as a single layer between the xylem and phloem in the young stem. It eventually forms a complete ring.

i) Formation of cambial ring:

The intrafascicular cambium is the cambium cells found between the primary xylem and primary phloem in dicot stems. The interfascicular cambium is formed when the cells of medullary rays next to this intrafascicular cambium become meristematic. As a result, a continuous ring of cambium forms.

ii) Activity of the cambial ring:

The cambial ring becomes active and starts cutting off new cells from both the inside and outside. Secondary xylem develops from cells cut off towards the pith, while secondary phloem develops from cells cut off towards the periphery. The inner side of the cambium is often more active than the outer side. As a result, secondary xylem is formed in greater quantities than the secondary phloem, forming a compact mass. The persistent development and accumulation of secondary xylem gradually crushes the primary and secondary phloems. The principal xylem, on the other hand, is mostly intact at or near the centre.The cambium sometimes produces a narrow band of parenchyma that runs in radial directions through the secondary xylem and secondary phloem. These are the secondary medullary rays.

iii) Springwood and autumn wood:

Cambium activity is influenced by a variety of physiological and environmental variables. Climate conditions in temperate zones are rarely consistent throughout the year. The cambium is particularly active in the spring and produces a significant number of xylary components with larger vessels. Springwood, also known as earlywood, is formed during this season. Autumn wood or latewood is formed when the cambium is less active in the winter and produces fewer xylary components with thin channels. Springwood is lighter in color and denser, whereas fall wood is darker and denser. An annual ring is made up of two types of wood that appear as alternate concentric rings.Annual rings in a cut stem can be used to estimate the age of a tree.

iv) Heartwood and sapwood:

The deposition of organic components such as tannins, resins, oils, gums, aromatic chemicals, and essential oils in the middle or innermost layers of the stem causes the majority of secondary xylem in ancient trees to be dark brown. These compounds make it tough, long-lasting, and resistant to bacteria and insects. Heartwood is a zone made up of dead components with heavily lignified walls. The stem is supported mechanically by the heartwood, which does not conduct water. Sapwood refers to the lighter-colored portion of the secondary xylem. It helps to transport water and minerals from the root to the leaf.

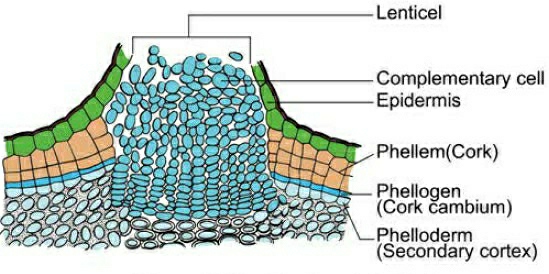

B.Cork Cambium:The outer cortical and epidermal layers break down as the stem grows in girth due to vascular cambium activity, and they must be replaced to create new protective cell layers. As a result, additional meristematic tissue is known as cork cambium or phellogen forms, usually in the cortical region, sooner or later. Phellogen is made up of several layers. It is made up of cells that are tiny, thin-walled, and practically rectangular. Both sides of the cell are cut off by Phellogen. Inner cells differentiate into secondary cortex or phelloderm, whereas exterior cells differentiate into cork or phellem. Due to suberin deposition in the cell wall, the cork is impenetrable to water. Secondary cortical cells are parenchymatous. The periderm is the combination of phellogen, phellem, and phelloderm.

Pressure goes up on the remaining layers peripheral to phellogen due to cork cambium activity, and these layers eventually die and peel off. Secondary phloem is included in the phrase "bark," which is a non-technical term that refers to all tissues outside of the vascular cambium. Periderm and secondary phloem are two forms of tissue that makeup bark. Early or soft bark refers to bark that forms early in the season. Late or hard bark develops toward the end of the season. Instead of cork cells, the phellogen breaks off tightly packed parenchymatous cells on the outer surface in some areas. These parenchymatous cells quickly break the epidermis, generating lenticels, which are lens-shaped holes.Lenticels allow gas exchange between the outside atmosphere and the stem's internal tissue. Most woody trees have these.

C. Secondary Growth in Roots:

The vascular cambium in dicot roots is entirely secondary in origin. It develops from tissue right beneath the phloem bundles, a piece of pericycle tissue, and above the protoxylem, forming a complete and continuous wavy ring that eventually becomes circular. The next events are similar to those outlined before for a dicotyledon stem. Gymnosperm stems and roots also experience secondary growth. Monocotyledons, on the other hand, do not have secondary growth. Secondary growth usually results in a thickening of the root diameter due to the addition of vascular tissue. When cells in the residual procambium and sections of the pericycle begin to make periclinal divisions, secondary growth begins. Periclinal divisions begin only in the pericycle cells opposite the xylem sites. The vascular cambium is formed by the inner layer of cells. The pericycle is the outer layer that is retained. Around the primary xylem, the vascular cambium is continuous. The periclinal division of the vascular cambium continues. If the daughter cells divide towards the core of the root, they become secondary xylem cells, and if they divide towards the outer surface of the root, they become secondary phloem cells.The periderm, which comes from the pericycle and replaces the epidermis, forms an outer protective layer on certain roots. The pericycle restores its meristematic nature and divides periclinallyonce more and thus forms the phellogen or cork cambium. To the outside of the plant, the cork cambium generates phellum cells (cork cells). At maturity, these cells are lifeless. They've been suberized, which makes the cells water-resistant. Phellum cells in cross-section are neatly organized into files. The phelloderm, a mature tissue made up of live cells, is likewise produced by the cork cambium.

ACME SMART PUBLICATION

ACME SMART PUBLICATION