- Books Name

- Kaysons Academy Maths Foundation Book

- Publication

- Kaysons Publication

- Course

- JEE

- Subject

- Maths

Chapter -5

Lines And Angles

Basic Terms and Definitions

Recall that a part (or portion) of a line with two end points is called a line-segment and a part of a line with one end point is called a ray. Note that the line segment AB is denoted by AB, and its length is denoted by AB. The ray AB is denoted by AB , and a line is denoted by AB . However, we will not use these symbols, and will denote the line segment AB, ray AB, length AB and line AB by the same symbol, AB. The meaning will be clear from the context. Sometimes small letters l , m, n, etc. will be used to denote lines.

If three or more points lie on the same line, they are called collinear points; otherwise they are called non-collinear points.

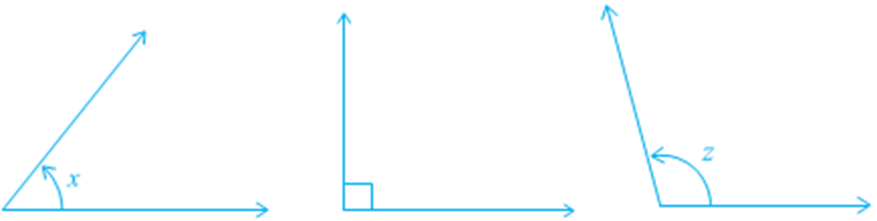

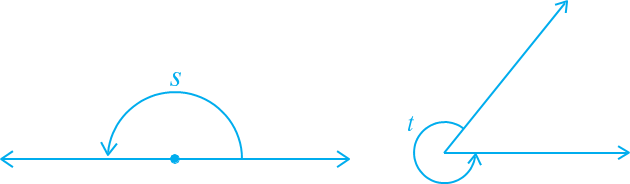

Recall that an angle is formed when two rays originate from the same end point. The rays making an angle are called the arms of the angle and the end point is called the ver. tax of the angle. You have studied different types of angles, such as acute angle, right angle, obtuse angle, straight angle and reflex angle in earlier classes.

Types of Angles

An acute angle measures between 0° and 90°, whereas a right angle is exactly equal to 90°. An angle greater than 90° but less than 180° is called an obtuse angle. Also, recall that a straight angle is equal to 180°. An angle which is greater than 180° but less than 360° is called a reflex angle. Further, two angles whose sum is 90° are called complementary angles, and two angles whose sum is 180° are called supplementary angles.

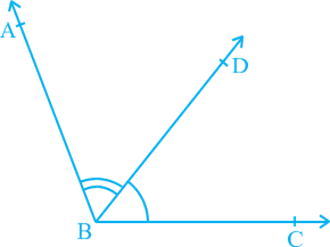

You have also studied about adjacent angles in the earlier classes. Two angles are adjacent, if they have a common vertex, a common arm and their non-common arms are on different sides of the common arm. In Fig., ∠ ABD and ∠ DBC are adjacent Angles. Ray BD is their common arm and point B is their common vertex. Ray BA and ray BC are non common arms. Moreover, when two angles are adjacent, then their sum is always equal to the angle formed by the two non- common arms. So, we can write.

Adjacent angles

∠ ABC = ∠ ABD + ∠ DBC.

Note that ∠ ABC and ∠ ABD are not adjacent angles. Why? Because their non- common arms BD and BC lie on the same side of the common arm BA.

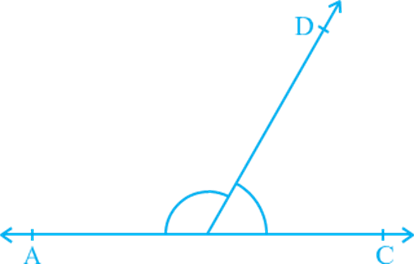

If the non-common arms BA and BC in, form a line then it will look like Fig. 6.3. In this case, ∠ ABD and ∠ DBC are called linear pair of angles.

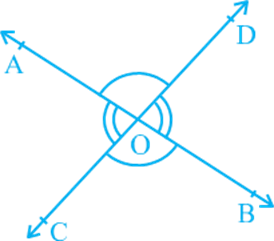

You may also recall the vertically opposite angles formed when two lines, say AB and CD, intersect each other, say at the point O. There are two pairs of vertically opposite angles.

One pair is ∠AOD and ∠BOC. Can you find the other pair?

Intersecting Lines and Non-intersecting Lines

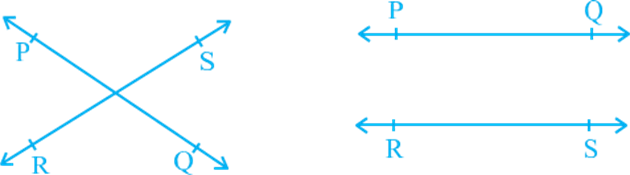

Draw two different lines PQ and RS on a paper. You will see that you can draw them in two different ways as shown in Fig.

Recall the notion of a line that it extends indefinitely in both directions. Lines PQ and RS in Fig. 6.5 (i) are intersecting lines and in Fig. 6.5 (ii) are parallel lines. Note that the lengths of the common perpendiculars at different points on these parallel lines are the same. This equal length is called the distance between two parallel lines.

Pairs of Angles

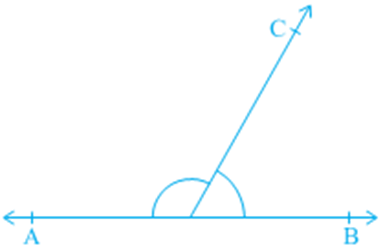

In Section 6.2, you have learnt the definitions of some of the pairs of angles such as complementary angles, supplementary angles, adjacent angles, linear pair of angles, etc. Can you think of some relations between these angles? Now, let us find out the relation between the angles formed when a ray stands on a line. Draw a figure in which a ray stands on a line as shown in. Name the line as AB and the ray as OC. What are the angles formed at the point O? They are ∠ AOC, ∠ BOC and ∠ AOB.

Can we write ∠ AOC + ∠ BOC = ∠ AOB? (1)

Yes! (Why? Refer to adjacent angles in Section 6.2)

What is the measure of ∠ AOB? It is 180°. (Why?) (2)

From (1) and (2), can you say that ∠ AOC + ∠ BOC = 180°? Yes! (Why?)

From the above discussion, we can state the following Axiom:

Axiom 6.1: If a ray stands on a line, then the sum of two adjacent angles so formed is 180°.

Recall that when the sum of two adjacent angles is 180°, then they are called a Linear pair of angles.

In Axiom 6.1, it is given that ‘a ray stands on a line’. From this ‘given’, we have concluded that ‘the sum of two adjacent angles so formed is 180°’. Can we write Axiom 6.1 the other way? That is, take the ‘conclusion’ of Axiom 6.1 as ‘given’ and the ‘given’ as the ‘conclusion’. So it becomes:

(A) If the sum of two adjacent angles is 180°, then a ray stands on a line (that is, the non-common arms form a line).

Kaysons Publication

Kaysons Publication