Lesson-10

Kathmandu

By Vikram Seth (An extract from ‘Heaven Lake’)

Kathmandu Introduction

Vikram Seth, a writer, hitchhiked from China to India via Tibet and Nepal and wrote about it in his book 'Heaven Lake.' In this extract from the book, we learn about his visit to Kathmandu, Nepal's capital.

Kathmandu Summary

Vikram Seth, the author, describes his visit to Kathmandu, Nepal's capital, in this chapter. He went to two temples there: the Pashupatinath temple, which is a Hindu pilgrimage site, and the Baudhnath temple, which is a Buddhist holy place

The Pashupatinath temple was only open to Hindus. With priests, tourists, pilgrims, and animals crowding the area, there was a lot of chaos. The holy river Bagmati, which flows close to the temple, was polluted by washerwomen washing clothes in it, children bathing in it, and residents throwing dry, withered flowers in it. Small shrines protruded from the stone platform, and it was said that when the platform emerged completely, the goddess would emerge from it, bringing the Kaliyug to an end. The scene at the Baudhnath temple was diametrically opposed to the one at the Pashupatinath temple. It was a massive white dome surrounded by an outer road. The atmosphere was serene and peaceful. Outside the temple, there was a Tibetan market where Tibetan refugees sold bags, clothing, and jewellery.

Kathmandu has a wide range of attractions. It has religious significance, is a business hub, and is a popular tourist destination. Postcards, antiques, chocolates, imported cosmetics, camera film rolls, and utensils are all available in shops. In the streets, a variety of sounds could be heard. The music blowing from the radios, the honking of car horns, the ringing of bicycle bells, the mooing of cows as they obstructed the passing motorcycles, and the screaming vendors selling their wares. To digest, Vikram ate a marzipan bar, a roasted corn on the cob garnished with lemon juice, salt, and chilli powder, and drank coca cola. He also purchased some love story comics and a Reader's Digest.

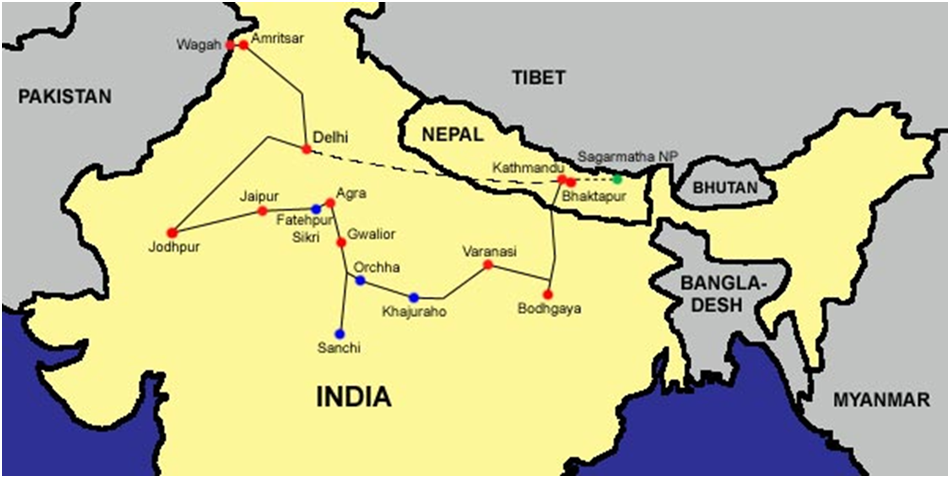

On his way back to Delhi, he considered taking an unusual route. It would be a bus or train ride to Patna, followed by a boat ride up the Ganga river to Allahabad. It would be followed by a boat ride down the Yamuna to Delhi. He abandoned the plan because he was tired and instead took a direct flight from Kathmandu to New Delhi the next day.

He noticed a flute seller outside his hotel. He held a pole with many flutes protruding from it like thorns on a porcupine's body. The man stood quietly, taking out a different flute, playing it for a few minutes before replacing it with another. Every now and then, he'd sell one of them mindlessly. He played the flute in a meditative manner. He wasn't like the other hawkers who yelled to sell their wares. The music of the flute drew the writer in. Flutes are played in many parts of the world, and their appearance, names, and the music they produce vary. A flute's sound is similar to that of a human voice because it is played by exhaling the breadth, and its music also pauses when a person inhales a breadth.

Kathmandu Lesson Explanation

I get a cheap room in the centre of town and sleep for hours. The next morning, with Mr Shah’s son and nephew, I visit the two temples in Kathmandu that are most sacred to Hindus and Buddhists.

Vikram rented a cheap, affordable hotel room and slept for a few hours because he was tired from the journey. The next morning, he and Mr. Shah's son and nephew went to two temples in Kathmandu. One of the temples was a Hindu pilgrimage, while the other was a Buddhist pilgrimage.

At Pashupatinath (outside which a sign proclaims ‘Entrance for the Hindus only’) there is an atmosphere of ‘febrile confusion’. Priests, hawkers, devotees, tourists, cows, monkeys, pigeons and dogs roam through the grounds. We offer a few flowers. There are so many worshippers that some people trying to get the priest’s attention are elbowed aside by others pushing their way to the front. A princess of the Nepalese royal house appears; everyone bows and makes way. By the main gate, a party of saffron-clad Westerners struggle for permission to enter. The policeman is not convinced that they are ‘the Hindus’ (only Hindus are allowed to enter the temple). A fight breaks out between two monkeys. One chases the other, who jumps onto a shivalinga, then runs screaming around the temples and down to the river, the holy Bagmati, that flows below. A corpse is being cremated on its banks; washerwomen are at their work and children bathe. From a balcony a basket of flowers and leaves, old offerings now wilted, is dropped into the river. A small shrine half protrudes from the stone platform on the river bank. When it emerges fully, the goddess inside will escape, and the evil period of the Kaliyuga will end on earth.

- Proclaims: make known publicly or officially

- Febrile confusion: hurried activity; complete chaos

- Saffron – clad westerners: foreigners dressed as sadhus

- Corpse: dead body

- Wilted: dry and withered

- Shrine: a place of worship

- Protrudes: comes out

- Kalyug: it is the fourth and last stages or time period of a Mahayuga. It started with the end of Mahabharata when Lord Krishna left the Earth.

A sign outside the Pashupatinath temple stated that entry into the temple was restricted to Hindus only. Outside the temple, there was chaos as priests, hawkers, devotees, tourists, and various animals moved around. In the temple, the writer and his friends offered a few flowers. There was a rush of pilgrims, and they were elbowing each other to get ahead and see the priest. When a royal princess appeared, everyone moved to the side and bowed to her. At the main entrance, a group of foreigners dressed as sadhus in saffron tried to gain entry into the temple. The guard refused them entry because he knew they were not Hindus. Then he saw two monkeys fighting, and one chased the other, who jumped onto a shivling, ran around the temple, and eventually arrived at the banks of the holy Bagmati river, which flows next to the temple. He witnessed a body being cremated, washerwomen washing clothes, and children bathing in the river. When a basket of dry withered flowers was thrown into the river from a building's balcony, the writer noticed how polluted it was. A small temple protruded from the riverbank platform. It is said that when the temple fully emerges, the goddess within will emerge, and the time period of the Kalyug will be ended by her.

At the Boudhnath stupa, the Buddhist shrine of Kathmandu, there is, in contrast, a sense of stillness. Its immense white dome is ringed by a road. Small shops stand on its outer edge: many of these are owned by Tibetan immigrants; felt bags, Tibetan prints and silver jewellery can be bought here. There are no crowds: this is a haven of quietness in the busy streets around.

- Immigrants: a person who comes to live permanently in a foreign country.

- Haven: a safe place

The writer then describes the Boudhanath temple, which is a sacred place for Buddhists. There was a sense of calm about the place. A huge white – coloured dome was surrounded by a road. On the side of the road, there was a Tibetan market where Tibetan immigrants set up shop selling felt bags, printed dresses, and silver jewellery. There were no crowds, and unlike the Pashupatinath temple, the Baudhnath temple was calm and quiet, despite the busy streets that surrounded it.

Kathmandu is vivid, mercenary, religious, with small shrines to flower-adorned deities along the narrowest and busiest streets; with fruit sellers, flute sellers, hawkers of postcards; shops selling Western cosmetics, film rolls and chocolate; or copper utensils and Nepalese antiques. Film songs blare out from the radios, car horns sound, bicycle bells ring, stray cows low questioningly at motorcycles, vendors shout out their wares. I indulge myself mindlessly: buy a bar of marzipan, a corn on- the-cob roasted in a charcoal brazier on the pavement (rubbed with salt, chilli powder and lemon); a couple of love story comics, and even a Reader’s Digest. All this I wash down with Coca Cola and a nauseating orange drink, and feel much the better for it.

- Deities: gods and goddesses

- Cows low: the ‘moo’ sound made by cows

- Marzipan: a sweet made with grated almonds

- Brazier: open stove

- Wash down: to drink something after a meal to digest it

- Nauseating: sickening

The author describes Kathmandu, a city with a wide range of attractions. It is a business centre with many shrines and deities decorated with flowers on the narrow, busy streets. Tourists can buy fruits, flutes, and postcards from hawkers. There are numerous shops selling imported cosmetics, film rolls from old cameras, chocolates, copper utensils, and Nepalese antiques. Many different sounds can be heard, including radio music, car horns, bicycle bells, cow moos, and screaming vendors selling their wares. The author purchased a bar of marzipan and a corn on the cob roasted over a charcoal fire by a roadside vendor. He topped it with lemon juice, salt, and chilli powder. He also purchased some love story comic books and a Reader's Digest magazine. After finishing everything, he drank Coca-Cola, an aerated drink that would aid in digestion.

I consider what route I should take back home. If I were propelled by enthusiasm for travel per se, I would go by bus and train to Patna, then sail up the Ganges past Benaras to Allahabad, then up the Yamuna, past Agra to Delhi. But I am too exhausted and homesick; today is the last day of August. Go home, I tell myself: move directly towards home. I enter a Nepal Airlines office and buy a ticket for tomorrow’s flight.

- Propelled: drive or push something forward

- Per se: by itself

He considered taking a more adventurous route back home. It'd be a bus or train ride to Patna. From there, he'd take a boat down the Ganga and cross Benaras on his way to Allahabad. He planned to sail down the Yamuna River from Allahabad, cross Agra, and arrive in Delhi. He abandoned his daring journey and decided to take a flight from Kathmandu to New Delhi because he was exhausted. He bought a ticket for the next day's flight from the Nepal Airlines office.

I look at the flute seller standing in a corner of the square near the hotel. In his hand is a pole with an attachment at the top from which fifty or sixty bansuris protrude in all directions, like the quills of a porcupine. They are of bamboo: there are cross-flutes and recorders. From time to time he stands the pole on the ground, selects a flute and plays for a few minutes. The sound rises clearly above the noise of the traffic and the hawkers’ cries. He plays slowly, meditatively, without excessive display. He does not shout out his wares. Occasionally he makes a sale, but in a curiously offhanded way as if this were incidental to his enterprise. Sometimes he breaks off playing to talk to the fruit seller. I imagine that this has been the pattern of his life for years.

- Meditatively: thoughtfully

- Offhanded: casual; not showing much interest in something

The author saw a flute vendor selling various bansuris. He was not like the other hawkers. Outside the hotel, they were standing in a corner of the square. He was holding a pole with an attachment on top. It had 50-60 flutes stuck in it. It resembled a porcupine's thorny body. There were bamboo flutes, as well as cross flutes and recorders. The man would keep the pole on the ground and play various flutes for short periods of time. Only the music of the flute could be heard from him. He played it meditatively, not wanting to draw attention to himself. He sold one flute at a time but did not appear to be interested in making a good sale. He'd take breaks to talk with the fruit vendor standing next to him. This appeared to be his routine for many years.

I find it difficult to tear myself away from the square. Flute music always does this to me: it is at once the most universal and most particular of sounds. There is no culture that does not have its flute — the reed neh, the recorder, the Japanese shakuhachi, the deep bansuri of Hindustani classical music, the clear or breathy flutes of South America, the high-pitched Chinese flutes. Each has its specific fingering and compass. It weaves its own associations. Yet to hear any flute is, it seems to me, to be drawn into the commonality of all mankind, to be moved by music closest in its phrases and sentences to the human voice. Its motive force too is living breath: it too needs to pause and breathe before it can go on.

- Fingering: way of placing the fingers to play different notes

- Compass: here, range

The music of the flute enchanted Vikram, and he couldn't leave. Flute music, he believes, is the most universal sound. Flutes are played in many different regions and have various names and varieties, such as the Shakuhachi in Japan, the deep bansuri of Hindustani classical music, the clear, breathy flutes in South America, and the high – pitched flutes in China. Each flute has a unique way of being played, and the sound varies in pitch and depth. The most common sound that emerges from a flute is the sound of human voice. When playing the bansuri by mouth, the player exhales into the flute to produce music, and when he pauses to take a breath, the music of the flute also stops.

That I can be so affected by a few familiar phrases on the bansuri, surprises me at first, for on the previous occasions that I have returned home after a long absence abroad, I have hardly noticed such details, and certainly have not invested them with the significance I now do.

He is surprised that the bansuri's sounds have such an impact on him. Never before had he paid such close attention to something as the flute seller and his wares.

About the Author

Vikram Seth CBE is a novelist and poet from India. He attended exclusive Indian schools before graduating from Oxford's Corpus Christi College (B.A., 1975). In 1978, he earned a master's degree in economics from Stanford University in the United States, and he later attended Nanjing University in China.

ACERISE INDIA

ACERISE INDIA