- Books Name

- CBSE Class 7 Social Science Book

- Publication

- Param Publication

- Course

- CBSE Class 7

- Subject

- Social Science

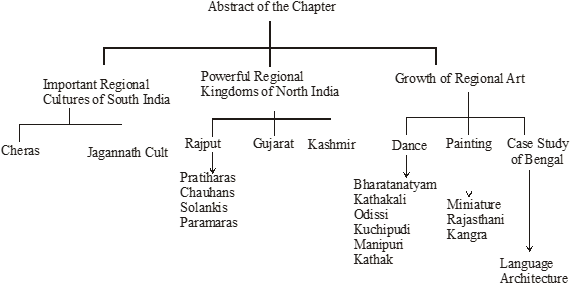

* INTRODUCTION

What we understand as regional cultures today are often the product of complex processes of intermixing of local traditions with ideas from other parts of the subcontinent. As we will see, some traditions appear specific to some regions, others seem to be similar across regions, and yet others derive from older practices in a particular area, but take a new form in other regions.

* Important Regional Cultures of South India

1. The Cheras and the Development of Malayalam

(i) The Chera kingdom of Mahodayapuram was established in the ninth century in the south-western part of the peninsula, part of present-day Kerala.

(ii) It is likely that Malayalam was spoken in this area. The rulers introduced the Malayalam language and script in their inscriptions.

(iii) The temple theatre of Kerala, which is traced to this period, borrowed stories from the Sanskrit epics. Interestingly enough, a fourteenth-century text, the Lilatilakam, dealing with grammar and poetics, was composed in Manipravalam-literally, “diamonds and corals” referring to the two languages, Sanskrit and the regional language.

2. Rulers and Religious Traditions: The Jagannatha Cult

(i) In other regions, regional cultures grew around religious traditions. The best example of this process is the cult of Jagannatha (literally, lord of the world, a name for Vishnu) at Puri, Orissa.

(ii) In the twelfth century, Anantavarman, decided to erect a temple for Purushottama jagannatha at Puri. In 1230, king anangabhima III dedicated his kingdom to the deity and proclaimed himself as the “deputy” of the god.

(iii) All those who conquered Orissa, such as the Mughals, the Marathas and the English East India Company, attempted to gain control over the temple. They felt that this would make their rule acceptable to the local people.

* Powerful Regional Kingdoms of North India

1. The Rajputs and Traditions of Heroism

In the nineteenth century, the region that constitutes most of present-day Rajasthan, was called Rajputana by the British. There were four distinct lineages that could be traced into the Chahamanas or Chauhans, Pratiharas, Solankis and Paramaras.

2. The Prathiharas.

The Gurajara Pratihara dynasty ruled over the area around modern Jodhpur in the 6th century AD. Their kingdom soon extended over Rajasthan, Gujarat, and up to Ujjain. They were engaged in constant wars with the Palas of Bengal and the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan. The Pratiharas ruled up to about 1036.

3. The Chahamanas or Chauhans

The Chauhans ruled in Sambhar near Jaipur in the 7th century AD. Later they conquered Delhi, Part of Punjab and Bundelkhand. Prithviraja III was the last ruler of the Chauhans.

4. The Solankis

The Solankis ruled over Anhilwara in modern Gujarat. Mularaja was their first king. Jayasimha was one of the greatest Solanki kings, who extended his territories into Rajasthan and Gwalior and defeated the Paramaras of Malwa.

5. The Paramaras

The Paramaras ruled in Malwa. Dhara was their capital and Krishnaraja was their first king.

Bhoja was the greatest king, who built a college at Dhara, and the city of Bhojpur near Bhopal.

* Ideals of Rajput Rulers

(i) The Rajputs are often recognised as contributing to the distinctive culture of Rajasthan. These cultural traditions were closely linked with the ideals and aspirations of rulers. From about the eighth century, most of the present-day state of Rajasthan was ruled by various Rajput families.

(ii) These rulers cherished the ideal of the hero who fought valiantly, often choosing death on the battlefield rather than face defeat.

(iii) Stories about Rajput heroes were recorded in poems and songs, which were recited by specially trained minstrels. These preserved the memories of heroes and were expected to inspire others to follow their example. Ordinary people were also attracted by these stories.

* Condition of women in Rajput Society

Sometimes women figure as the “cause” for conflicts, as men fought with one another to either “win” or “protect” women. Women are also depicted as following their heroic husbands in both life and death - there are stories about the practice of sati or the immolation of widows on the funeral pyre of their husbands. So those who followed the heroic ideal often had to pay for it with their lives.

1. Kashmir :

In the 7th century, the Nagarkota Dynasty established itself as the rulers of Kashmir. The most famous king was Lalitaditya Muktapida who conquered part of Punjab and defeated Yashovarman of Kannauj.

2. Gujarat :

Gujarat was conquered by Uluch Khan in 1299 after defeating Raja Karna Vaghela. From that time it was ruled for a long time by Muslim governors appointed by the Delhi Sultans. During the reign of Firoz Tughlaq, the situation in Gujarat became worse and several governors.

* Growth of Regional Art

1. Dance

(A) Beyond Regional Frontiers: The Story of Kathak:

The term Kathak is derived from katha, a word used in Sanskrit and other languages for story.

* Characteristics of Kathak

(i) The kathaks were originally a caste of story-tellers in temples of north India, who embellished their performances with gestures and songs.

(ii) Kathak began evolving into a distinct mode of dance in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries with the spread of the bhakti movement.

(iii) The legends of Radha-Krishna were enacted in folk plays called rasa lila, which combined folk dance with the basic gestures of the kathak story-tellers.

(iv) It developed in two traditions style. Subsequently. It developed in two traditions or gharanas : one in the courts of Rajasthan (Jaipur) and the other in Lucknow. Under the patronage of Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Awadh, it grew into a major art form.

(v) Emphasis was laid on intricate and rapid footwork, elaborate costumes, as well as on the enactment of stories.

(B) “Classical” Dances:

What is classical ?

(i) We define something as classical if it deals with a religious theme.

(ii) We consider it classical because it appears to require a great deal of skill acquired through long years of training.

(iii) It is classical because it is performed according to rules that are laid down, and variations are not encouraged.

It is worth remembering that many dance forms that are classified as “folk” also share several of the characteristics considered typical of “classical” forms. So, while the use of the term “Classical” may suggest that these forms are superior, this need not always be literally true.

Other dance forms that are recognised as classical at present are :

- Bharatanatyam (Tamil Nadu)

- Kathakali (Kerala)

- Odissi (Orissa)

- Kuchipudi (Andhra Pradesh)

- Manipuri (Manipur)

2. Painting

(A) Miniature Painting:

Miniatures (as their very name suggests) are small-sized paintings, generally done in water colour on cloth or paper. The earliest miniatures were on palm leaves or wood. Some of the most beautiful of these, found in western India, were used to illustrate Jaina texts. The Mughal emperors Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan patronised highly skilled painters.

Features of Miniature Painting:

(i) Primarily illustrated manuscripts contained historical accounts and poetry.

(ii) These were generally painted in brilliant colours and portrayed court scenes, scenes of battle or hunting, and other aspects of social life.

(iii) They were often exchanged as gifts and were viewed only by an exclusive few-the emperor and his close associates.

(B) Rajasthani Painting;

Features

(i) With the decline of the Mughal Empire, many painters moved out to the courts of the emerging regional states. As a result Mughal artistic taste influenced the regional courts of the Deccan and the Rajput courts of Rajasthan.

(ii) At the same time, they retained and developed their distinctive characteristics.

(iii) Portraits of rulers and court scenes came to be painted, following the Mughal example.

(iv) Besides, themes from mythology and poetry were depicted at centres such as Mewar, Jodhpur, Bundi, Kota and Kishangarh.

(C) Kangra Painting:

Features:

(i) Another region that attracted miniature paintings was the Himalayan foothills around the modern-day state of Himachal Pradesh.

(ii) By the late seventeenth century this region had developed a bold and intense style of miniature painting called Basohli.

(iii) The most popular text to be painted here was Bhanudatta’s Rasamanjari.

(iv) Nadir Shah’s invasion and the conquest of Delhi in 1739 resulted in the migration of Mughal artists to the hills to escape the uncertainties of the plains. Here they found ready patrons which led to the founding of the Kangra school of painting.

(v) The source of inspiration was the Vaishnavite traditions. Soft colours including cool blues and greens, and a lyrical treatment of themes distinguished Kangra painting.

* A Closer Look: Bengal The Growth of a Regional Language and Architecture

While Bengali is now recognised as a language derived from Sanskrit, early Sanskrit texts (mid-first millennium BCE) suggest that the people of Bengal did not speak Sanskritic languages.

(A) How did the new language (Bengali) emerge

(i) From the fourth-third centuries BCE, commercial ties began to develop between Bengal and Magadha (south Bihar), which may have led to the growing influence of Sanskrit.

(ii) During the fourth century the Gupta rulers established political control over north Bengal and began to settle Brahmanas in this area. Thus, the linguistic and cultural influence from the mid-Ganga valley became stronger.

(iii) From the eighth century, Bengal became the centre of a regional kingdom under the Palas. In 1586, when Akbar conquered Bengal, it formed the nucleus of the Bengal suba. While Persian was the language of administration, Bengali developed as a regional language. Although Bengali is derived from Sanskrit, it passed through several stages of evolution.

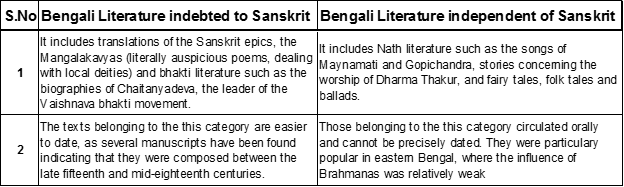

Bengali literature may be divided into 2 categories

(B) Pirs and Temples

From the sixteenth century, people began to migrate in large numbers from the less fertile western Bengal to the forested and marshy areas of south-eastern Bengal. As they moved eastwards, they cleared forests and brought the land under rice cultivation. Gradually, local communities of fisherfolk and shifting cultivators, often tribals, merged with the new communities of peasants.

This coincided with the establishment of Mughal control over Bengal with their capital in the heart of the eastern delta at Dhaka. Officials and functionaries received land and often set up mosques that served as centres for religious transformation in these areas.

Who were Pirs ?

The early settlers sought some order and assurance in the unstable conditions of the new settlements. These were provided by community leaders, who also functioned as teachers and adjudicators and were sometimes ascribed with supernatural powers. People referred to them with affection and respect as pirs.

This term included saints or Sufis and other religious personalities, daring colonisers and deified soldiers, various Hindu and Buddhist deities and even animistic spirits. The cult of pirs became very popular and their shrines can be found everywhere in Bengal.

Temples:

Bengal also witnessed a temple-building spree from the late fifteenth century, which culminated in the nineteenth century.

Why were temples built in Bengal

(i) Temples and other religious structures were often built by individuals or groups who were becoming powerful-to both demonstrate their power and proclaim their piety.

(ii) Many of the modest brick and terracotta temples in Bengal were built with the support of several “low” social groups, such as the Kolu (oil pressers) and the Kansari (bell metal workers).

(iii) The coming of the European trading companies created new economic opportunities; many families belonging to these social groups availed of these. As their social and economic position improved. The proclaimed their status through the construction of temples.

(iv) When local deities, once worshipped in thatched huts in villages, gained the recognition of the Brahmanas, their images began to be housed in temples, The temples began to copy the double-roofed (dochala) or four-roofed (chauchala) structure of the thatched huts. This led to the evolution of the typical Bengali style in temple architecture.

* Features of Bengali Temples

(i) In the comparatively more complex four-roofed structure, four triangular roofs placed on the four walls move up to converge on a curved line or a point.

(ii) Temples were usually built on a square platform.

(iii) The interior was relatively plain, but the outer walls of many temples were decorated with paintings, ornamental tiles or terracotta tablets.

(iv) In some temples, particularly in Vishnupur in the Bankura district of West Bengal, such decorations reached a high degree of excellence.

(C) Fish as Food

(i) Bengal is a riverine plain which produces plenty of rice and fish. Understandably, these two items figure prominently in the menu of even poor Bengalis. Fishing has always been an important occupation and Bengali literature contains several references to fish. What is more, terracotta plaques on the walls of temples and viharas (Buddhist monasteries) depict scenes of fish being dressed and taken to the market in baskets.

(ii) Brahamanas were not allowed to eat non-vegetarian food, but the popularity of fish in the local diet made the Brahmanical authorities relax this prohibition for the Bengal Brahmanas. The Brihaddharma Purana, a thirteenth-century Sanskrit test from Bengal, permitted the local Brahmanas to eat certain varieties of fish.

Illustration 1

Write any two features of miniature painting ?

Solution

(i) These were generally painted in brilliant colours and portrayed court scenes, scenes of battle or hunting, and other aspects of social life.

(ii) They were often exchanged as gifts and were viewed only by an exclusive few-the emperor and his close associates.

Illustration 2

Why were the Brahmans allowed the eat fish in Bengal ?

Solution

Brahmans were not allowed to eat non-vegetarian food, but the popularity of fish in the local diet made the Brahmanical authorities relax this prohibition for the Bengal Brahmanas.

Param Publication

Param Publication