- Books Name

- CBSE Class 7 Social Science Book

- Publication

- Param Publication

- Course

- CBSE Class 7

- Subject

- Social Science

* INTRODUCTION

Aurangzeb’s reign of more than half-a-century ended in March 1707. In that month and year, Aurangzeb died at Ahmednagar in Deccan. With his death, India again entered a period of crisis for the next half a century. Lacking any succession policy, there ensued a war of succession, in which two of Aurangzeb’s sons and three grandsons were killed, before 60 year old Shah Alam took the name of Bahadur Shah, and ascended the throne. Soon the Mughal Empire began to witness rapid decline and disintegration.

* The Crisis of the Empire and the Later Mughals

- The Mughal Empire reached the height of its success and started facing a variety of crises towards the closing years of the seventeenth century. These were caused by a number of factors. Emperor Aurangzeb had depleted the military and financial resources of his empire by fighting a long war in the Deccan.

- The efficiency of the imperial administration broke down. It became increasingly difficult for the later Mughal emperors to keep a check on their powerful mansabdars.

- Nobles appointed as governors (subadars) often controlled the offices of revenue and military administration (diwani and faujdari) as well. This gave them extraordinary political, economic and military powers over vast regions of the Mughal Empire. As the governors consolidated their control over the provinces, the periodic remission of revenue to the capital declined.

- Peasant and zamindari rebellions in many parts of northern and western India added to these problems. These revolts were sometimes caused by the pressures of mounting taxes, by powerful chieftains to consolidate their own positions.

- In the midst of this economic and political crisis, the ruler of Iran, Nadir Shah, sacked and plundered the city of Delhi in 1739 and took away immense amounts of wealth. This invasion was followed by a series of plundering raids by the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali, who invaded north India five times between 1748 and 1761.

- The empire was further weakened by competition amongst different groups of nobles. They were divided into two major groups or factions, the Iranis and Turanis (nobles of Turkish descent).

- The worst possible humiliation came when two Mughal emperors, Farrukh Siyar (1713-1719) and Alamgir II (1754-1759) were assassinated, and two others Ahmad Shah (1748-1754) and Shah Alam II (1759-1816) were blinded by their nobles.

* Emergence of New States

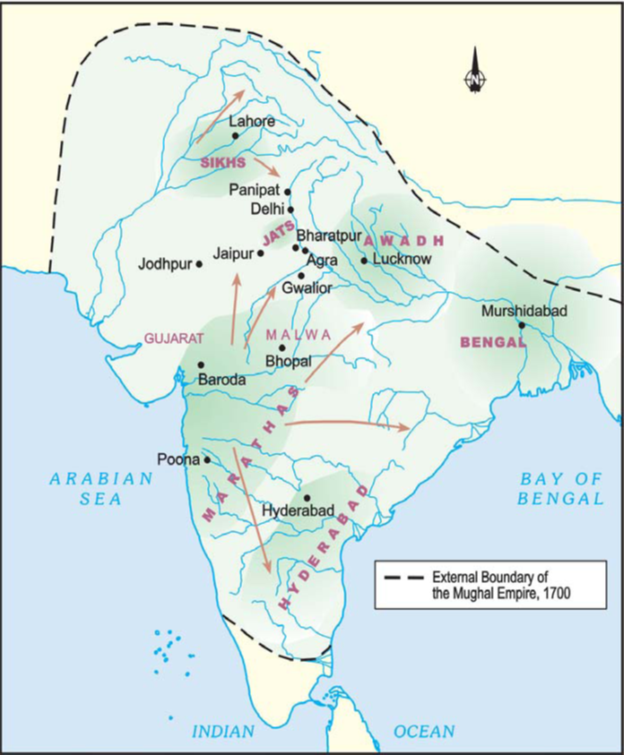

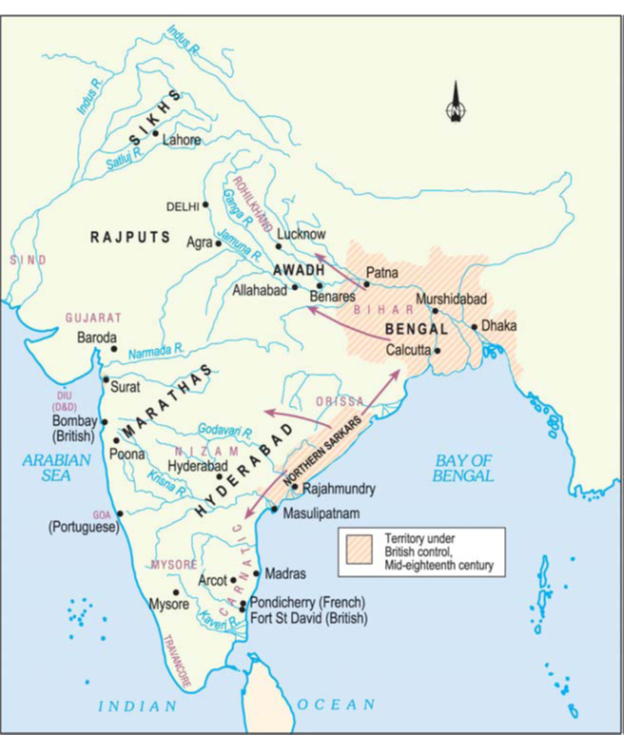

Through the eighteenth century, the Mughal Empire gradually fragmented into a number of independent, regional states. Broadly speaking the states of the eighteenth century can be divided into three overlapping groups:

(1) States that were old Mughal provinces like Awadh, Bengal and Hyderabad. Although extremely powerful and quite independent, the rulers of these states did not break their formalties with the Mughal emperor.

(2) States that had enjoyed considerable independence under the Mughals as watan jagirs. These included several Rajput principalities.

(3) The last group included states under the control of Marathas, Sikhs and others like the Jats. These were of differing sizes and had seized their independence from the Mughals after a long-drawn armed struggle.

* The Old Mughal Provinces

- Amongst the states that were carved out of the old Mughal provinces in the eighteenth century, three stand out very prominently. These were Awadh, Bengal and Hyderabad.

- All three states were founded by members of the high Mughal nobility who had been governors of large provinces - Sa‘adat Khan (Awadh), Murshid Quli Khan (Bengal) and Asaf Jah (Hyderabad).

- All three had occupied high mansabdari positions and enjoyed the trust and confidence of the emperors. Both Asaf Jah and Murshid Quli Khan held a zat rank of 7,000 each, while Sa’adat Khan’s zat was 6,000.

* Hyderabad

- Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah, the founder of Hyderabad state, was one of the most powerful members at the court of the Mughal Emperor Farrukh Siyar.

- He was entrusted first with the governorship of Awadh, and later given charge of the Deccan, during 1720-22 Asaf Jah already had full control over its political and financial administration.

- Taking advantage of the turmoil in the Deccan and the competition amongst the court nobility, he gathered power in his hands and became the actual ruler of that region.

- Asaf Jah brought skilled soldiers and administrators from northern India who welcomed the new opportunities in the south.

- He appointed mansabdars and granted jagirs. Although he was still a servant of the Mughal emperor, he ruled quite independently without seeking any direction from Delhi or facing any interference. The Mughal emperor merely confirmed the decisions already taken by the Nizam.

- The state of Hyderabad was constantly engaged in a struggle against the Marathas to the west and with independent Telugu warrior chiefs (nayakas) of the plateau. The ambitions of the Nizam to control the rich textile-producing areas of the Coromandel coast in the east were checked by the British who were becoming increasingly powerful in that region.

* Awadh

- Burhan-ul-Mulk Sa‘adat Khan was appointed subadar of Awadh in 1722 and founded a state which was one of the most important to emerge out of the break-up of the Mughal Empire.

- Awadh was a prosperous region, controlling the rich alluvial Ganga plain and the main trade route between north India and Bengal. Burhan-ul-Mulk also held the combined offices of subadari, diwani and faujdari.

- Burhan-ul-Mulk tried to decrease Mughal influence in the Awadh region by reducing the number of office holders (jagirdars) appointed by the Mughals.

- The accounts of jagirdars were checked to prevent cheating and the revenues of all districts were reassessed by officials appointed by the Nawab’s court. He seized a number of Rajput zamindaris and the agriculturally fertile lands of the Afghans of Rohilkhand.

- The state depended on local bankers and mahajans for loans.

- The revenue farmers (ijaradars) agreed to pay the state a fixed sum of money. Local bankers guaranteed the payment of this contracted amount to the state. In turn, the revenue-farmers were given considerable freedom in the assessment and collection of taxes.

- These developments allowed new social groups, like moneylenders and bankers, to influence the management of the state’s revenue system, something which had not occurred in the past.

* Bengal

- Bengal gradually broke away from Mughal control under Murshid Quli Khan who was appointed as the naib, deputy to the governor of the province. Although never a formal subadar, Murshid Quli Khan very quickly seized all the power that went with that office.

- In an effort to reduce Mughal influence in Bengal he transferred all Mughal jagirdars to Orissa and ordered a major reassessment of the revenues of Bengal. Revenue was collected in cash.

- The formation of a regional state in eighteenth century Bengal therefore led to considerable change amongst the zamindars.

- The close connection between the state and bankers - noticeable in Hyderabad and Awadh as well - was evident in Bengal under the rule of Alivardi Khan (r. 1740-1756). During his reign the banking house of Jagat Seth became extremely prosperous.

* Three common features amongst these states.

(a) First, though many of the larger states were established by erstwhile Mughal nobles they were highly suspicious of some of the administrative systems that they had inherited, in particular the jagirdari system.

(b) Second, their method of tax collection differed. Rather than relying upon the officers of the state, all three regimes contracted with revenue-farmers for the collection of revenue. The practice of ijaradari, thoroughly disapproved of by the Mughals, spread all over India in the eighteenth century. Their impact on the countryside differed considerably.

(c) The third common feature in all these regional states was their emerging relationship with rich bankers and merchants. These people lent money to revenue farmers, received land as security and collected taxes from these lands through their own agents. Throughout India the richest merchants and bankers were gaining a stake in the new political order.

* The Watan Jagirs of the Rajputs

- Many Rajput kings, particularly those belonging to Amber and Jodhpur, had served under the Mughals with distinction. In exchange, they were permitted to enjoy considerable autonomy in their watan jagirs.

- Ajit Singh, the ruler of Jodhpur, was also involved in the factional politics at the Mughal court.

- These influential Rajput families claimed the subadari of the rich provinces of Gujarat and Malwa. Raja Ajit Singh of Jodhpur held the governorship of Gujarat and Sawai Raja Jai Singh of Amber was governor of Malwa. These offices were renewed by Emperor Jahandar Shah in 1713. They also tried to extend their territories by seizing portions of imperial territories neighbouring their watans.

- Nagaur was conquered and annexed to the house of Jodhpur, while Amber seized large portions of Bundi.

- Sawai Raja Jai Singh founded his new capital at Jaipur and was given the subadari of Agra in 1722.

- Maratha campaigns into Rajasthan from the 1740s put severe pressure on these principalities and checked their further expansion.

* Seizing Independence

* The Sikhs

- Several battles were fought by Guru Gobind Singh against the Rajput and Mughal rulers, both before and after the institution of the Khalsa in 1699.

- After his death in 1708, the Khalsa rose in revolt against the Mughal authority under Banda Bahadur’s leadership, declared their sovereign rule by striking coins in the name of Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh, and established their own administration between the Sutlej and the Jamuna.

- Banda Bahadur was captured in 1715 and executed in 1716.

- Under a number of able leaders in the eighteenth century, the Sikhs organized themselves into a number of bands called jathas, and later on misls.

- Their combined forces were known as the grand army (dalkhalsa).

- The entire body used to meet at Amritsar at the time of Baisakhi and Diwali to take collective decisions known as resolutions of the Guru (gurmatas).

- A system called rakhi was introduced, offering protection to cultivators on the payment of a tax of 20 per cent of the produce.

- The Khalsa declared their sovereign rule by striking their own coin again in 1765.

- The Sikh territories in the late eighteenth century extended from the Indus to the Jamuna but they were divided under different rulers. One of them, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, reunited these groups and established his capital at Lahore in 1799.

* The Marathas

- Shivaji (1627-1680) carved out a stable kingdom with the support of powerful warrior families (deshmukhs).

- Groups of highly mobile, peasant-pastoralists (kunbis) provided the backbone of the Maratha army.

- After Shivaji’s death, effective power in the Maratha state was wielded by a family of Chitpavan Brahmanas who served Shivaji’s successors as Peshwa (or principal minister).

- Poona became the capital of the Maratha kingdom.

- The Marathas developed a very successful military organisation. Their success lay in bypassing the fortified areas of the Mughals, by raiding cities and by engaging Mughal armies in areas where their supply lines and reinforcements could be easily disturbed.

- Between 1720 and 1761, the Maratha Empire expanded. It gradually chipped away at the authority of the Mughal Empire.

- Malwa and Gujarat were seized from the Mughals by the 1720s.

- By the 1730s, the Maratha king was recognised as the overlord of the entire Deccan peninsula. He possessed the right to levy chauth and sardeshmukhi in the entire region.

- After raiding Delhi in 1737 the frontiers of Maratha domination expanded rapidly: into Rajasthan and the Punjab in the north; into Bengal and Orissa in the east; and into Karnataka and the Tamil and Telugu countries in the south.

- Expansion brought enormous resources, but it came at a price. These military campaigns also made other rulers hostile towards the Marathas. As a result, they were not inclined to support the Marathas during the third battle of Panipat in 1761.

- Alongside endless military campaigns, the Marathas developed an effective administrative system as well.

- Once conquest had been completed and Maratha rule was secure, revenue demands were gradually introduced taking local conditions into account.

- Agriculture was encouraged and trade revived. This allowed Maratha chiefs (sardars) like Sindhia of Gwalior, Gaekwad of Baroda and Bhonsle of Nagpur the resources to raise powerful armies.

- Ujjain expanded under Sindhia’s patronage and Indore under Holkar’s.

- These cities were large and prosperous and functioned as important commercial and cultural centres.

- The silk produced in the Chanderi region now found a new outlet in Poona, the Maratha capital.

- Burhanpur which had earlier participated in the trade between Agra and Surat now expanded its hinterland to include Poona and Nagpur in the south and Lucknow and Allahabad in the east.

* The Jats

- Under their leader, Churaman, they acquired control over territories situated to the west of the city of Delhi, and by the 1680s they had begun dominating the region between the two imperial cities of Delhi and Agra. For a while they became the virtual custodians of the city of Agra.

- The Jats were prosperous agriculturists, and towns like Panipat and Ballabhgarh became important trading centres in the areas dominated by them.

- Under Suraj Mal, the kingdom of Bharatpur emerged as a strong state. When Nadir Shah sacked Delhi in 1739, many of the city’s notables took refuge there. His son Jawahir Shah had 30,000 troops of his own and hired another 20,000 Maratha and 15,000 Sikh troops to fight the Mughals.

- While the Bharatpur fort was built in a fairly traditional style, at Dig the Jats built an elaborate garden palace combining styles seen at Amber and Agra. Its buildings were modelled on architectural forms first associated with royalty under Shah Jahan.

Param Publication

Param Publication