- Books Name

- (English) Hornbill & Snapshot Class-11

- Publication

- PathSet Publications

- Course

- CBSE Class 11

- Subject

- English

Ranga’s Marriage

Introduction

The story depicts the life in Indian villages in the past when child marriage was a common practice. Ranga’s Marriage is an interesting story of how a person manipulates to get a young boy married to an eleven-year-old girl in a village. The story dates back to the early days of British rule when English was not used in a big way. Rangappa, the son of a village accountant returns from Bangalore after his studies. His homecoming after six months makes a big event. The curious villagers gather outside Ranga’s house to see how much the boy is changed. But they see no change in the boy. The narrator discusses the issue of marriage with Ranga. He is piqued to hear his ideas about marriage. He resolves to get the boy married to a very young and immature 11-year-old girl Ratna. He seeks the support of Shastri’s astrology to bring Ratna round. And Ranga forgets his idealism and settles down happily.

Summary

Ten years ago when the village accountant sent his son Ranga to Bangalore for studies, the situation in the village was different. People never used to use English words while talking in Kannada, their mother tongue. But now they do it with an abominable pride. For instance, Rama Rao’s son was not ashamed to use the word ‘change’ while buying some firewood from a woman who knew no English, thereby creating confusion.

Now people are so fond of foreign language and education that Ranga’s homecoming is made a big affair. People crowd his house to see if he has changed. They return home on finding no significant change in him. The narrator is particularly happy to find the boy still quite cultured as he respectfully does ‘namaskara’. The narrator spontaneously blesses him saying ‘May you get married soon.’

But the boy is not ready for marriage, he says. He is of the opinion that one should better remain a bachelor than marry a young girl, as the custom of the village is. The narrator is disappointed to hear this, but as he sincerely wants Ranga to get married and settle to be of some service to society, he does not lose heart. He takes a vow to get him married, and that to a young girl of 11 by the name of Ratna, Rama Rao’s niece, who has of late come to Hosahalli to stay for a few days.

Now the narrator plans to make the prospective bride and the bridegroom meet each other. So he does this by asking Rao’s wife to send Ratna to his house to fetch buttermilk. As Ratna arrives she is asked to sing. As planned at that very moment Ranga arrives and gets mesmerized by Ratna’s singing and almost instantly falls in love with her being oblivious of his theories regarding child marriage. The narrator, from his experience, notices this quite well but purposely disappoints Ranga by saying that Ratna is married.

The next morning the narrator meticulously plots with Shastri, the fortune teller, to trap Ranga and have him marry Ratna. He tutors him in what is to be said and done when he will bring the boy to him. The narrator finds Ranga miserable that day. The latter complains of headaches and the narrator suggests that they visit Shastri. Thereupon Ranga is taken to Shastri who cleverly reacts by saying that their visit has been a surprise. The narrator acts foolishly forgetting what he is supposed to say but Shastri cleverly manages the scene.

Everything goes well as per the plan. Shyama, the narrator, asks Shastri what might be worrying the boy. Shastri calculates throwing his cowries and suggests that it is about a girl. On further calculation, he suggests that the girl’s name has a connection with something found in the ocean. The narrator asks if it could be ‘Kamala’. Then he suggests ‘Pachchi’, meaning moss. When Shastri hints at‘ pearl’ or ‘Ratna’, the narrator becomes jubilant and Ranga is amazed. Shyama further asks if there is any chance of negotiation of the marriage bearing any fruit, to which Shastri answered affirmatively. But once again the narrator pours water on Ranga’s hopes by saying that Ratna is married.

However, on the way, the narrator enters Rama Rao’s house and comes out of the house to inform Ranga that Ratna is unmarried and the previous information about her marriage was wrong. Now visibly Ranga’s joys have no limits. When the narrator asks him whether whatever the astrologer told is right, he admits that it is true and further adds that there is more truth in astrology than he thought.

Later the narrator informs Shastri about the success story and makes a sarcastic comment about astrology. But Shastri is not ready to accept. He says that the former gave only the hints and whatever he said was the result of his calculation. Whatever the case might be, Ranga finally gets married to Ratna and fathers two children, moreover, Ratna is now eight months pregnant. The narrator is invited to the third birth anniversary of Ranga’s child, who was named after the narrator as ‘Shyama’. On finding this, the narrator mildly chides Ranga saying that he knows that it is the English custom to name the child after someone one likes, but it is not fair to name him ‘Shyama’ because he is fair complexioned.

All said and done, it is interesting to find how Ranga forgets what he learned about happy marriages in cities and gives in to the far deeper influences the village customs and traditions have on him. And why not, is it easy to do away with all that one learns so unconsciously day and night in the society one grows up in?

Ranga’s Marriage Lesson Explanation

Ranga, the accountant’s son, is one of the rare breeds among the village folk who has been to the city to pursue his studies. When he returns to his village from the city of Bangalore, the crowds mill around his house to see whether he has changed or not. His ideas about marriage are now quite different—or are they?

Word meaning

Rare breed- a person or thing with characteristics that are uncommon among their kind; a rarity

The lesson revolves around Ranga, the village accountant’s son who had just come back from Bangalore. At the news of his arrival, the villagers gather at his home to analyze if he had changed or not and what is his perception about marriage. Everyone was so excited because, during those days, not everyone used to get a chance to go to cities for studying.

When you see this title, some of you may ask, “Ranga’s Marriage?” Why not “Ranganatha Vivaha” or “Ranganatha Vijaya?” Well, yes. I know I could have used some other mouth-filling one like “Jagannatha Vijaya” or “Girija Kalyana.” But then, this is not about Jagannatha’s victory or Girija’s wedding. It’s about our own Ranga’s marriage and hence no fancy title. Hosahalli is our village. You must have heard of it. No? What a pity! But it is not your fault. There is no mention of it in any geography book. Those sahibs in England, writing in English, probably do not know that such a place exists, and so make no mention of it. Our own people forget about it. You know how it is —they are like a flock of sheep. One sheep walks into a pit, the rest blindly follow it. When both, the sahibs in England and our own geographers, have not referred to it, you cannot expect the poor cartographer to remember to put it on the map, can you? And so there is not even the shadow of our village on any map

Word meaning

Vivaha- Marriage

Vijaya- Victory

Girija- female (here)

Kalyana- beautiful, lovely, auspicious in Sanskrit

Sahib- a polite title or form of address for a man

Like a flock of sheep- a group of people behaving in the same way or following what others are doing

Cartographer- a person who draws or produces maps

The narrator expects the readers to be questioning the simplicity of the title “Ranga’s Marriage”. He feels readers might be thinking of fancier titles like “Ranganatha Vivaha”, “Ranganatha Vijaya” or “Girija Kalyana”. He clarifies that although he had options of keeping such elaborate names, the reason why he chose the basic and casual one is that the story is about “our Ranga” as in, someone who is very close and dear to him. They live in a village called Hosahalli in Mysore. Not many people know of it and the narrator does not blame them because there is no trace of it in the geography books. Even the Englishmen have no idea about the place but they are also not to blame because our citizens too are completely ignorant about his village. He refers to the people as “sheep” who blindly follow each other and do not use their logic or brain to justify or invent things. At last, he feels the cartographer is also not to be held responsible. As a result, there is no trace of their village on the map.

Sorry, I started somewhere and then went off in another direction. If the state of Mysore is to Bharatavarsha what the sweet karigadabu is to a festive meal, then Hosahalli is to Mysore State what the filling is to the karigadabu. What I have said is absolutely true, believe me. I will not object to your questioning it but I will stick to my opinion. I am not the only one who speaks glowingly of Hosahalli. We have a doctor in our place. His name is Gundabhatta. He agrees with me. He has been to quite a few places. No, not England. If anyone asks him whether he has been there, he says, “No, annayya , I have left that to you. Running around like a flea-pestered dog is not for me. I have seen a few places in my time, though.” As a matter of fact, he has seen many.

Word meaning

Bharatvarsha- India

Karigadabu- a South Indian fried sweet filled with coconut and sugar

Annayya- (in Kannada) a respectful term for an elder

Flea-pestered dog- A flea-pestered dog does not stick to one place but keeps roaming everywhere.Flea-pestered means being infested by fleas and ticks which can cause uncontrollable itching in animals

The narrator feels apologetic for getting carried away and deviating from the topic. He then again throws light upon the significance of the village Hosahalli. He says it is just as important as Mysore is to India, Karigadabu to a festive meal and filling is to Karigadabu. Thus, he can’t highlight its importance anymore. Not only him, but the doctor named Gundabhatta feels the same. The doctor has been to many places except England but he still loves Hosahalli. However, an outsider might contest this but the narrator claims to stick to his opinion of the place.

We have some mango trees in our village. Come visit us, and I will give you a raw mango from one of them. Do not eat it. Just take a bite. The sourness is sure to go straight to your brahmarandhra . I once took one such fruit home and chutney was made out of it. All of us ate it. The cough we suffered from, after that! It was when I went for the cough medicine that the doctor told me about the special quality of the fruit. Brahmarandhra-(in Kannada) the soft part in a child’s head where skull bones join later. Here, used as an idiomatic expression to convey the extreme potency of sourness. In Sanskrit, “Brahmarandhra” means the hole of Brahman. It is the dwelling house of the human soul.

Then he tells the readers about their special mango trees in the village whose mangoes are famous for their special quality. He once took the fruit at home to make chutney and everyone suffered from a bad cough after eating it. It was only when he went to see the doctor that he told him about the quality of mangoes of Hosahalli. The narrator asks the readers to take a bite and assures them that the sourness of the mango will be felt by them till the top of their head (where Brahmarandhra is located).

Just as the mango is special, so is everything else around our village. We have a creeper growing in the ever-so-fine water of the village pond. Its flowers are a feast to behold. Get two leaves from the creeper when you go to the pond for your bath, and you will not have to worry about not having leaves on which to serve the afternoon meal. You will say I am rambling. It is always like that when the subject of our village comes up. But enough. If any one of you would like to visit us, drop me a line. I will let you know where Hosahalli is and what things are like here. The best way of getting to know a place is to visit it, don’t you agree?

Word meaning

Behold- see or observe (someone or something, especially of remarkable or impressive nature)

Rambling- (of writing or speech) lengthy and confused or inconsequential

Not only is the mangoes, everything in and around this village is remarkable. The creeper growing in the pond and its flowers are also special. One can even serve an afternoon meal on its leaves, all you need to do is to grab two leaves when you are on your way to the pond to bathe. After speaking highly of his village, the narrator says if anyone wishes to see for himself/herself, one must contact him. He will help them to reach there. Also, he feels that there is no better way to know a place than to visit it.

What I am going to tell you is something that happened ten years ago. We did not have many people who knew English, then. Our village accountant was the first one who had enough courage to send his son to Bangalore to study. It is different now. There are many who know English. During the holidays, you come across them on every street, talking in English. Those days, we did not speak in English, nor did we bring in English words while talking in Kannada. What has happened is disgraceful, believe me. The other day, I was in Rama Rao’s house when they bought a bundle of firewood. Rama Rao’s son came out to pay for it. He asked the woman, “How much should I give you?” “Four pice,” she said. The boy told her he did not have any “change” and asked her to come the next morning. The poor woman did not understand the English word “change” and went away muttering to herself. I too did not know. Later, when I went to Ranga’s house and asked him, I understood what it meant.

The narrator then brings about a comparison as to how things were different ten years ago when not many people knew or spoke English. Neither did people send their children to big cities like Bangalore to study. Back then, only the village accountant had the courage to send his son to Bangalore. According to the author, those times were simpler. He justifies his claim by telling an incident where he was at Rama Rao’s house and they had just bought a bundle of firewood from an old lady. Rama told her to come the next morning as he did not have any chance at the moment. The poor old lady did not know what “change” meant and she went away whispering to herself. Neither did the narrator know its meaning. It was only when he went to Ranga’s house that he told him.

This priceless commodity, the English language, was not so widespread in our village a decade ago. That was why Ranga’s homecoming was a great event. People rushed to his doorstep announcing, “The accountant’s son has come,” “The boy who had gone to Bangalore for his studies is here, it seems,” and “Come, Ranga is here. Let’s go and have a look.”

However, ten years ago, English was not commonly spoken in this village and when the villagers came to know that Ranga, the accountant’s son was coming home from Bangalore, everyone got excited and rushed to his home to have a glance at him.

Attracted by the crowd, I too went and stood in the courtyard and asked, “Why have all these people come? There’s no performing monkey here.” A boy, a fellow without any brains, said, loud enough for everyone to hear, “What are you doing here, then?” A youngster, immature and without any manners. Thinking that all these things were now of the past, I kept quiet.

Fascinated by all the crowd, the narrator too, went there and asked people as to why they were gathered because he couldn’t see anything entertaining happening there like a monkey performing. A boy “without brains” shouted loud enough for everyone to hear and in a rude way. The narrator called him immature

Seeing so many people there, Ranga came out with a smile on his face. Had we all gone inside, the place would have turned into what people call the Black Hole of Calcutta. Thank God it did not. Everyone was surprised to see that Ranga was the same as he had been six months ago when he had first left our village. An old lady who was near him ran her hand over his chest, looked into his eyes, and said, “The janewara is still there. He hasn’t lost his caste.” She went away soon after that. Ranga laughed.

Word meaning

Janewara- (in Kannada) the sacred thread worn by Brahmins

All the people were waiting outside Ranga’s house because the place would look like the “Black Hole of Calcutta” if they all went inside. By saying this, the narrator means that there were so many people that the house would have fallen short to accommodate them all. Thus, Ranga came outside with a smile on his face. Everyone was so amazed to see that Ranga had not changed a bit after he left 6 months ago. An old lady even went to the extent of running her hands through his chest to check for a sacred thread. However, she went away after confirming that he had not forgotten about his caste.

Once they realized that Ranga still had the same hands, legs, eyes, and nose, the crowd melted away, like a lump of sugar in a child’s mouth. I continued to stand there. After everyone had gone, I asked, “How are you, Rangappa? Is everything well with you?” It was only then that Ranga noticed me. He came near me and did a namaskara respectfully, saying, “I am all right, with your blessings.”

Once the villagers realized that Ranga did not change even after moving to the city, they disappeared as fast as a lump of sugar does in a child’s mouth. The narrator waited till the crowd cleared and asked him about his well-being. Ranga noticed him and replied with full respect in a traditional way. Ranga had not noticed the narrator in the crowd before that moment.

I must draw your attention to this aspect of Ranga’s character. He knew when it would be to his advantage to talk to someone and rightly assessed people’s worth. As for his namaskara to me, he did not do it like any present-day boy—with his head up towards the sun, standing stiff like a pole without joints, jerking his body as if it was either a wand or a walking stick. Nor did he merely fold his hands. He bent low to touch my feet. “May you get married soon,” I said, blessing him. After exchanging a few pleasantries, I left.

Ranga was very well-behaved and well-aware as to who could benefit him. He was one of those who could analyze someone’s worth rightfully. For how he greeted the narrator, he bent low and touched his feet thereby seeking his blessings. It was not the present-day namaskara where children would do it casually, it was a proper, traditional one. The narrator blessed him that he might get married soon and then, left.

That afternoon, when I was resting, Ranga came to my house with a couple of oranges in his hand. A generous, considerate fellow. It would be a fine thing to have him marry, settle down and be of service to society, I thought. For a while, we talked about this and that. Then I came to the point. “Rangappa, when do you plan to get married?” “I am not going to get married now,” he said. “Why not?” “I need to find the right girl. I know an officer who got married only six months ago. He is about thirty and his wife is twenty-five, I am told. They will be able to talk lovingly to each other. Let’s say I married a very young girl. She may take my words spoken in love as words spoken in anger. Recently, a troupe in Bangalore staged the play Shakuntala. There is no question of Dushyantha falling in love with Shakuntala if she were young, as the present-day brides, is there? What would have happened to Kalidasa’s play? If one gets married, it should be to a girl who is mature. Otherwise, one should remain a bachelor. That’s why I am not marrying now.”

Word meaning

Considerate- thoughtful, concerned

Troupe- a group of dancers, actors, or other entertainers who tour different venues

That afternoon, Ranga visited the author with a few oranges which the narrator thought was quite thoughtful of him. Thinking of how nice Ranga is, the author thought it would be a good deed to have him married to a girl just as nice as him. They chatted for a while and then the narrator asked Ranga about his views on getting married. Ranga expresses that he doesn’t intend on marrying now because he intends on finding the right girl. He cites the example of an officer who got married at the age of thirty to a woman aged twenty-five. Now since these are both adults, they would understand each other’s actions and behavior. Whereas suppose the narrator finds a girl who is very young, she could misunderstand his words or actions because she is not mature enough. He even mentions the love story of Shakuntala and Dushyantha from Mahabharata and that he would not have fallen in love with Shakuntala if she were too young. In that case, Kalidasa’s play also would have not existed. That is why he intends on staying a bachelor's till he finds the right girl.

“Is there any other reason?” “A man should marry a girl he admires. What we have now are arranged marriages. How can one admire a girl with milk stains on one side of her face and wetness on the other, or so young that she doesn’t even know how to bite her fingers?” “One a neem fruit, the other, a bitter gourd.” “Exactly!” Ranga said, laughing. I was distressed that the boy who I thought would make a good husband, had decided to remain a bachelor. After chatting for a little longer, Ranga left. I made up my mind right then, that I would get him married. Rama Rao’s niece, a pretty girl of eleven, had come to stay with him. She was from a big town, so she knew how to play the veena and the harmonium. She also had a sweet voice. Both her parents had died, and her uncle had brought her home. Ranga was just the boy for her, and she was the most suitable bride for him.

Here, the narrator introduces us to a new character in the story named Ratna. She is eleven years old and is Rama Rao’s niece. She had lost both her parents so her uncle brought her from the big town to his home with him. She had a great voice and could play harmonium and veena. The narrator thought that Ranga and Ratna would make a great pair.

Since I was a frequent visitor to Rama Rao’s place, the girl was quite free with me. I completely forgot to mention her name! Ratna, it was. The very next morning I went to their house and told Rama Rao’s wife, “I’ll send some buttermilk for you. Ask Ratna to fetch it.” Ratna came. It was a Friday, so she was wearing a grand saree. I told her to sit in my room and requested her to sing a song. I sent for Ranga. While she was singing the song— Krishnamurthy, in front of my eyes — Ranga reached the door. He stopped at the threshold. He did not want the singing to stop but was curious to see the singer. Carefully, he peeped in. The light coming into the room was blocked. Ratna looked up and seeing a stranger there, abruptly stopped.

Word meaning

Threshold- a strip of wood or stone forming the bottom of a doorway and crossed in entering a house or a room

Ratna was quite familiar with the narrator as he visited Rama’s place frequently. The narrator thought of a plan to introduce Ratna to Ranga. He asked Rama to send Ratna to his place as he wanted to send some buttermilk for them. She came all dressed up. The narrator insisted upon her to sing a song while he sent someone to call Ranga. Just as she was singing, Ranga arrived at the door. Her melancholic voice touched his ears and thus, he did not want to interrupt the singing so he stood at the door. He was curious to see the singer and very cautiously he tried to have a look that disturbed the lighting in the room. On seeing a stranger, Ratna immediately stopped her singing.

Suppose you buy the best quality mango. You eat it slowly, savoring its peel, before biting into the juicy flesh. You do not want to waste any part of it. Before you take another bite, the fruit slips out of your hand and falls to the ground. How do you feel? Ranga’s face showed the same disappointment when the singing stopped. “You sent for me?” he asked as he came in and sat on a chair. Ratna stood at a distance, her head lowered. Ranga repeatedly glanced at her. Once, our eyes met, and he looked very embarrassed. No one spoke for a long while.

The narrator compares Ranga’s situation to the disappointment of dropping a best-quality mango on the floor just before having to truly enjoy it. It was as if something great had been stolen before one could fully enjoy it. Ranga asked the narrator why he called for him. Ratna was shy and thus, looked downward whereas Ranga stealthily glanced at her. There was an awkward silence in the room.

“It was my coming in that stopped the singing. Let me leave.” Words, mere words! The fellow said he would leave but did not make a move. How can one expect words to match actions in these days of Kaliyuga? Ratna ran inside, overcome by shyness. After things went a bit awkward, Ranga said that he feels it was his coming that stopped the singing so he must leave. However, he did not. The narrator makes fun of him because he had no intention of going. He jokes about it and says one cannot expect actions and words to match in the Kalyuga.

After a while, Ranga asked, “Who is that girl, swami?” “Who’s that inside?” the lion wanted to know. The he-goat who had taken shelter in the temple replied, “Does it matter who I am? I am a poor animal who has already eaten nine lions. I have vowed to eat one more. Tell me, are you male or female?” The lion fled the place in fear, it seems. Like the he-goat, I said, “What does it matter to either of us who she is? I’m already married and you aren’t the marrying kind.”

After a few minutes of awkward silence, Ranga finally asked the narrator about the girl. Now the narrator compares the situation with the infamous story of the he-goat and the lion where he is the he-goat and Ranga, the lion. The narrator replies very cleverly and intends on seeing Ranga’s interest in knowing about Ratna. Thus, he says that who she is, is not of that much importance because he is already married and Ranga doesn’t intend on marrying anytime soon.

Very hopefully, he asked, “She isn’t married, then?” His voice did not betray his excitement but I knew it was there. “She has married a year ago.” His face shriveled like roasted brinjal. After a while, Ranga left, saying, “I must go, I have work at home.” I went to our Shastri the next morning and told him, “Keep everything ready to read the stars. I’ll come later.” I tutored him in all that I wanted him to say. I found no change in Ranga when I met him that afternoon. “What’s the matter? You seem to be lost in thought,” I said. “Nothing, nothing’s wrong, believe me.” “Headache? Come, let’s go and see a doctor.”

Word meaning

Betray- portray (here)

Shriveled- shrunken and wrinkled; especially as a result of loss of moisture

Tutored- taught

Hearing the narrator’s reply, Ranga got excited, although he did not show it but was quite evident. Full of hope, he asks if she isn’t married yet to which the narrator replies that she is, probably a year ago. Ranga was disappointed and disheartened. It was clearly all over his face. He went away quoting some work. Our narrator, having staged certain liking in the mind of Ranga for Ratna, went on to complete his play. He went to the village Shastri and told him everything that had to be said and done. Then, he met Ranga that afternoon and he carried the same disappointment on his face. Upon asking if it’s a headache, the narrator tells him that they should go see a doctor.

“I have no headache. I’m my usual self.” “I went through the same thing when the process of choosing a girl for me was going on. But I don’t think that that could be a reason for your present condition.” Ranga stared at me. “Come, let’s go and see Shastri,” I suggested. “We will find out whether Guru and Shani are favorable for you or not.” Ranga accompanied me without any protest. As soon as Shastri saw me, he exclaimed, “What a surprise, Shyama! Haven’t seen you for a long time.”

Ranga insists that everything is fine with him and he is his normal self. The narrator, very wittily, makes a remark that he went through the same feelings when he was seeing girls for himself and immediately mentions that it could not be the reason for Ranga. Furthermore, he suggested that they go see Shastri to see if the stars (Guru for Jupiter and Shani for Saturn) are in their favor. Ranga went with him. On seeing Shastri ji, he implied not having seen the narrator in a long while, which is obviously not true as they had met before, the same morning.

Shyama is none other than your servant, the narrator of this tale. I got angry and shouted, “What? Only this morning…” Shastri completed my sentence, “You finished all your work and are now free to visit me.” Had he not done so, I would have ruined our plan by bursting like grains that are kept in the sun to dry. I was extremely careful of what I said afterward. Shastri turned to Ranga. “When did the young son of our accountant clerk come home? What can I do for him? It’s very rarely that he visits us.”

Here, the narrator reveals his pet name, Shyama as they called him in the village. The narrator felt that Shastri was lying because they saw each other that morning and thus he immediately responded. However, Shastri completed his sentence and saved the entire situation. Shyama realized what he was just about to do and took extra care from that moment. Shastri continued his role and acted surprised on seeing Ranga.

“Take out your paraphernalia. Our Rangappa seems to have something on his mind. Can you tell us what’s worrying him? Shall we put your science of astrology to the test?” There was an authority in my voice as I spoke to Shastri. He took out two sheets of paper, some cowries, and a book of palmyra leaves, saying, “Ours is an ancient science, ayya. There’s a story to it… But I won’t tell you that story now. This is not a harikatha that allows you to tell a story within a story… You may get bored. I’ll tell it to you some other time.”

Word meaning

Paraphernalia- trappings associated with a particular institution or activity that are regarded as superfluous

Cowries- a marine mollusk that has a glossy, brightly patterned domed shell with a long, narrow opening

Palmyra- palm tree

Harikatha- Story of Lord

The narrator asks the Shastri to take out all his tools to help solve whatever is going on in Ranga’s mind with full authority. Shastri took out his essentials and told them that this is all ancient science but he won’t recite it now because then they both would get bored but he does intend on telling it some other time.

Shastri moved his lips fast as he counted on his fingers and then asked, “What’s your star?” Ranga didn’t know. “Never mind,” Shastri indicated with a shake of his head. He did some more calculations before saying in a serious tone, “It’s about a girl.” I had been controlling my laughter all this while. But now I burst out laughing. I turned to Ranga. “Exactly what I had said.” “Who is the girl?” It was your humble servant who asked the question.

Shastri moved his lips while counting quickly and asked Ranga about his star which he did not know. Shastri implied that it’s manageable. He appeared to be doing certain calculations. After a moment, he indicated that Ranga has a girl on her mind. Even after trying his best, Shyama could not control his laughter. He thus, posed the question to Shastri asking about the details of the girl.

Shastri thought for a while before replying, “She probably has the name of something found in the ocean.” “Kamala?” “Maybe.”

“Could it be Pachchi, moss?” “Must it be moss if it’s not Kamala? Why not pearl or Ratna, the precious stone?” “Ratna? The girl in Rama Rao’s house is Ratna. Tell me, is there any chance of our negotiations bearing fruit?” “Definitely,” he said, after thinking for some time. There was a surprise on Ranga’s face. And some happiness. I noticed it. “But that girl is married…” I said, Then I turned to him. His face had fallen

Shastri thought and thought and replied that the girl is likely to have the name of something found in the ocean. Their guesses include Kamala, Pachchi, moss, pearl, and then suddenly Shastri said Ratna. All of it came together now to a girl named Ratna, who is the niece of Rama Rao. That’s it, Ranga was thinking about her only. Ranga was both surprised and happy because Shastri’s predictions were right. He immediately became disappointed when he recalled that she was married.

“I don’t know all that. There may be some other girl who is suitable. I only told you what our shastra indicated,” Shastri said. We left the place. On the way, we passed by Rama Rao’s house. Ratna was standing at the door. I went in alone and came out a minute later.

Shastri said that he did not know all that and there might be another suitable girl. To make it look real, Shastri interfered in their name guessing game and told them that he only told what can be read. Both of them left and crossed Rama Rao’s door where Shyama went to see Ratna for a minute and came back.

“Surprising. This girl isn’t married, it seems. Someone told me the other day that she was. What Shastri told us has turned out to be true after all! But Rangappa, I can’t believe that you have been thinking of her. Swear on the name of Madhavacharya and tell me, is it true what Shastri said?”

I do not know whether anyone else would have been direct. Ranga admitted, “There’s greater truth in that shastra than we imagine. What he said is absolutely true.”

Word meaning

Madhavacharya- an exponent of Vedantic philosophy from South India

When the narrator comes back, he announces that fortunately, Ratna is not married and someone might have wrongly conveyed it to him about that. The narrator expresses his amazement at the fact that he has been thinking about Ratna and asks him to swear upon the truth. To his surprise, Ranga told him the truth that whatever Shastri said is true. His belief in all the Shastras had strengthened.

Shastri was at the well when I went there that evening. I said, “So Shastrigale, you repeated everything I had taught you without giving rise to any suspicion. What a marvelous shastra yours is!” He didn’t like it at all. “What are you saying? What you said to me was what I could have found out myself from the shastras. Don’t forget, I developed on the hints you had given me.” Tell me, is this what a decent man says?

Word meaning

Marvelous- causing great wonder; extraordinary

Shyama went to see Shastri that evening when he was near the well and remarked about how well he did what Shyama told him to. Shastri seemed to not like what the narrator was saying. Thus, he says that whatever he said could very clearly be seen in the Shastras. He completely disagreed with having staged the entire conversation.

Rangappa had come the other day to invite me for dinner. “What’s the occasion?” I asked. “It’s Shyama’s birthday. He is three.” “It’s not a nice name —Shyama,” I said. “I’m like a dark piece of oil-cake. Why did you have to give that golden child of yours such a name? What a childish couple you are, Ratna and you! I know, I know, it is the English custom of naming the child after someone you like… Your wife is eight months pregnant now. Who’s there to help your mother to cook?” “My sister has come with her.” I went there for dinner. Shyama rushed to me when I walked in and put his arms around my legs. I kissed him on his cheek and placed a ring on his tiny little finger.

Now, the narrator takes us a few years forward where Ranga and Ratna are happily married, had a three-year-old son and Ratna was eight months pregnant. Ranga’s sister had come over to help them. It was Shyama’s birthday! Yes, the couple named their son after the narrator as it is a common foreign tradition to name your child after someone you truly admire. When the narrator went there for dinner, Shyama came running to him only to show his love by holding his leg. The narrator kissed him and gave him a ring.

Allow me to take leave of you, reader. I am always here, ready to serve you. You were not bored, I hope?

The narrator writes an ending note to all the readers hoping that they were not bored.

Lesson-3

Ranga’s Marriage

By Masti Venkatesha Iyengar

Ranga’s Marriage Introduction

Ranga, the accountant's son, is the main character of the story. He is given the opportunity to study outside of the village. The narrator takes you on a journey in which he changes Ranga's perception of marriage, how he staged their marriage with the assistance of a Shastri, and what role English has played in their village. The entire story contains amusing instances and references, and the narrator has ensured that your mind is kept occupied with the story.

Ranga’s Marriage Summary

Ranga, the accountant's son, returns to his village Hosahalli after a six-month absence. He had gone to Bangalore to further his studies, which not many people in the village have the opportunity to do. The entire village is excited to see Ranga, so they gather around his house to see how he has changed. The narrator has beautifully elaborated on their village Hosahalli and how every authority responsible failed to include it on maps. Moving on, he admires Ranga and wishes to marry him, but Ranga has very different views on marriage at the time. Ranga and Ratna, Rama Rao's eleven-year-old niece, are married for the first time, as staged by the Narrator.

The girl has a lovely voice and can also play the Veena and harmonium. The narrator initially informs him that she is married in order to observe how this affects Ranga. Ranga, as expected, was disappointed. The narrator then conscripted the village Shastri into saying things in his favour. He then took Ranga to see him, where he predicted that Ranga is thinking about a girl whose name is similar to something found in the ocean. Shyama, the narrator, believes her name is Ratna, but she is married. On their way back, they confirmed Ratna is not married, only to discover Ranga happy and full of hope.

The Shastri, on the other hand, was opposed to staging anything predetermined. He claims he said whatever his predictions indicated. Ranga and Ratna, on the other hand, are happily married with a three-year-old son named after the narrator. Ratna is also expecting another child.

Ranga’s Marriage Lesson Explanation

Ranga, the accountant’s son, is one of the rare breeds among the village folk who has been to the city to pursue his studies. When he returns to his village from the city of Bangalore, the crowds mill around his house to see whether he has changed or not. His ideas about marriage are now quite different—or are they?

- Rare breed- a person or thing with characteristics that are uncommon among their kind; a rarity

Ranga, the village accountant's son who had just returned from Bangalore, is the focus of the lesson. When word of his arrival spreads, the villagers gather at his house to see if he has changed and what his thoughts are on marriage. Everyone was excited because, back then, not everyone had the opportunity to study in cities.

WHEN you see this title, some of you may ask, “Ranga’s Marriage?” Why not “Ranganatha Vivaha” or “Ranganatha Vijaya?” Well, yes. I know I could have used some other mouth-filling one like “Jagannatha Vijaya” or “Girija Kalyana.” But then, this is not about Jagannatha’s victory or Girija’s wedding. It’s about our own Ranga’s marriage and hence no fancy title. Hosahalli is our village. You must have heard of it. No? What a pity! But it is not your fault. There is no mention of it in any geography book. Those sahibs in England, writing in English, probably do not know that such a place exists, and so make no mention of it. Our own people too forget about it. You know how it is —they are like a flock of sheep. One sheep walks into a pit, the rest blindly follow it. When both, the sahibs in England and our own geographers, have not referred to it, you can not expect the poor cartographer to remember to put it on the map, can you? And so there is not even the shadow of our village on any map.

- Vivaha- Marriage

- Vijaya- Victory

- Girija- female (here)

- Kalyana- beautiful, lovely,auspicious in Sanskrit

- Sahib- a polite title or form of address for a man

- Like a flock of sheep- a group of people behaving in the same way or following what others are doing

- Cartographer- a person who draws or produces maps

The narrator anticipates that readers will be perplexed by the title "Ranga's Marriage." He believes that readers may be thinking of fancier titles such as "Ranganatha Vivaha," "Ranganatha Vijaya," or "Girija Kalyana." He clarifies that, while he had the option of keeping such elaborate names, he chose the simple and casual one because the story is about "our Ranga," as in, someone very close and dear to him. They live in the Mysore village of Hosahalli. Few people are aware of it, and the narrator does not blame them because there is no mention of it in geography textbooks.

Even the Englishmen have no idea where he is, but they are not to blame because our citizens are also completely unaware of his village. He refers to people as "sheep" because they blindly follow each other and do not use logic or their brain to justify or invent things. Finally, he believes the cartographer should not be made responsible. As a result, their village is no longer visible on the map.

Sorry, I started somewhere and then went off in another direction. If the state of Mysore is to Bharatavarsha what the sweet karigadabu is to a festive meal, then Hosahalli is to Mysore State what the filling is to the karigadabu. What I have said is absolutely true, believe me. I will not object to your questioning it but I will stick to my opinion. I am not the only one who speaks glowingly of Hosahalli. We have a doctor in our place. His name is Gundabhatta. He agrees with me. He has been to quite a few places. No, not England. If anyone asks him whether he has been there, he says, “No, annayya , I have left that to you. Running around like a flea-pestered dog, is not for me. I have seen a few places in my time, though.” As a matter of fact, he has seen many.

- Bharatvarsha- India

- Karigadabu- a South Indian fried sweet filled with coconut and sugar

- Annayya- (in Kannada) a respectful term for an elder

- Flea-pestered dog- A flea- pestered dog does not stick to one place but keeps roaming everywhere.

- Flea-pestered means being infested by fleas and ticks which can cause uncontrollable itching in animals

The narrator regrets getting carried away and deviating from the topic. He then elaborates on the significance of the village Hosahalli. He considers it to be as important to India as Mysore is to India, Karigadabu is to a festive meal, and filling is to Karigadabu. As a result, he is no longer able to emphasise its significance. Not only him, but also the doctor Gundabhatta, feels the same way. The doctor has travelled to many places other than England, but he still adores Hosahalli. An outsider might disagree, but the narrator insists on his assertion of the place.

We have some mango trees in our village. Come visit us, and I will give you a raw mango from one of them. Do not eat it. Just take a bite. The sourness is sure to go straight to your brahmarandhra . I once took one such fruit home and a chutney was made out of it. All of us ate it. The cough we suffered from, after that! It was when I went for the cough medicine, that the doctor told me about the special quality of the fruit.

- Brahmarandhra-(in Kannada) the soft part in a child’s head where skull bones join later. Here, used as an idiomatic expression to convey the extreme potency of sourness. In Sanskrit, “Brahmarandhra” means the hole of Brahman. It is the dwelling house of the human soul.

Then he tells the readers about the village's special mango trees, whose mangoes are famous for their exceptional quality. He once brought the fruit home to make chutney, and everyone got a bad cough after eating it. He only told the doctor about the quality of Hosahalli mangoes when he went to see him. The narrator invites the readers to take a bite, assuring them that the sourness of the mango will be felt all the way to the top of their heads (where Brahmarandhra is located).

Just as the mango is special, so is everything else around our village. We have a creeper growing in the ever-so-fine water of the village pond. Its flowers are a feast to behold. Get two leaves from the creeper when you go to the pond for your bath, and you will not have to worry about not having leaves on which to serve the afternoon meal. You will say I am rambling. It is always like that when the subject of our village comes up. But enough. If any one of you would like to visit us, drop me a line. I will let you know where Hosahalli is and what things are like here. The best way of getting to know a place is to visit it, don’t you agree?

- Behold- see or observe (someone or something, especially of remarkable or impressive nature)

- Rambling- (of writing or speech) lengthy and confused or inconsequential

Everything in and around this village is remarkable, not just the mangoes. The creeper in the pond and its flowers are also noteworthy. Its leaves can even be used to serve an afternoon meal; simply grab two leaves on your way to the pond to bathe. After praising his village, the narrator says that anyone who wants to see for themselves/herself should contact him. He will assist them in getting there. In addition, he believes that there is no better way to learn about a place than to visit it.

What I am going to tell you is something that happened ten years ago. We did not have many people who knew English, then. Our village accountant was the first one who had enough courage to send his son to Bangalore to study. It is different now. There are many who know English. During the holidays, you come across them on every street, talking in English. Those days, we did not speak in English, nor did we bring in English words while talking in Kannada. What has happened is disgraceful, believe me. The other day, I was in Rama Rao’s house when they bought a bundle of firewood. Rama Rao’s son came out to pay for it. He asked the woman, “How much should I give you?” “Four pice,” she said. The boy told her he did not have any “change”, and asked her to come the next morning. The poor woman did not understand the English word “change” and went away muttering to herself. I too did not know. Later, when I went to Ranga’s house and asked him, I understood what it meant.

The narrator then draws a comparison to how things were ten years ago, when few people knew or spoke English. People also did not send their children to large cities like Bangalore to study. Only the village accountant had the strength and courage to send his son to Bangalore back then. Those were simpler times, according to the author. He supports up his claim by recounting an incident in which he was at Rama Rao's house and they had just purchased a bundle of firewood from an elderly lady. Rama told her to come back the next morning because he didn't have any change at the time. The poor old lady had no idea what "change" meant and went away quietly to herself. Neither did the narrator understand what it meant. He didn't tell Ranga until he arrived at his house.

This priceless commodity, the English language, was not so widespread in our village a decade ago. That was why Ranga’s homecoming was a great event. People rushed to his doorstep announcing, “The accountant’s son has come,” “The boy who had gone to Bangalore for his studies is here, it seems,” and “Come, Ranga is here. Let’s go and have a look.”

However, ten years ago, English was not widely spoken in this village, and when the villagers got to know that Ranga, the accountant's son, was returning home from Bangalore, everyone became excited and rushed to his house to take a look at him.

Attracted by the crowd, I too went and stood in the courtyard and asked, “Why have all these people come? There’s no performing monkey here.” A boy, a fellow without any brains, said, loud enough for everyone to hear, “What are you doing here, then?” A youngster, immature and without any manners. Thinking that all these things were now of the past, I kept quiet.

Fascinated by the crowd, the narrator went there and asked people why they were gathered because he couldn't see anything entertaining going on, such as a monkey performing. A boy "without brains" shouted loudly enough for everyone to hear and in an impolite manner. The narrator described him as immature.

Seeing so many people there, Ranga came out with a smile on his face. Had we all gone inside, the place would have turned into what people call the Black Hole of Calcutta. Thank God it did not. Everyone was surprised to see that Ranga was the same as he had been six months ago, when he had first left our village. An old lady who was near him, ran her hand over his chest, looked into his eyes and said, “The janewara is still there. He hasn’t lost his caste.” She went away soon after that. Ranga laughed.

- Janewara- (in Kannada) the sacred thread worn by Brahmins

Everyone was waiting outside Ranga's house because the place would resemble the "Black Hole of Calcutta" if everyone went inside. The narrator is implying that there were so many people that the house would have been too small to accommodate them all. As a result, Ranga smiled as he exited the house. Everyone was shocked to see that Ranga had not changed a bit since he had left 6 months before. An elderly lady even went so far as to run her hands through his chest in search of a sacred thread. She did, however, leave after assuring him that he had not forgotten about his caste.

Once they realised that Ranga still had the same hands, legs, eyes and nose, the crowd melted away, like a lump of sugar in a child’s mouth. I continued to stand there.

After everyone had gone, I asked, “How are you, Rangappa? Is everything well with you?” It was only then that Ranga noticed me. He came near me and did a namaskara respectfully, saying, “I am all right, with your blessings.”

When the villagers realised Ranga had not changed even after moving to the city, they vanished as quickly as a lump of sugar in a child's mouth. The narrator waited for the crowd to disperse before asking about his well-being. Ranga noticed him and responded in a traditional manner, with full respect. Ranga had missed the narrator in the crowd until that moment.

I must draw your attention to this aspect of Ranga’s character. He knew when it would be to his advantage to talk to someone and rightly assessed people’s worth. As for his namaskara to me, he did not do it like any present-day boy—with his head up towards the sun, standing stiff like a pole without joints, jerking his body as if it was either a wand or a walking stick. Nor did he merely fold his hands. He bent low to touch my feet. “May you get married soon,” I said, blessing him. After exchanging a few pleasantries, I left.

Ranga was well-mannered and well-aware of who could help him. He was one of those who could accurately assess someone's worth. He greeted the narrator by bending low and touching his feet, seeking his blessings. It wasn't the kind of namaskara that kids do nowadays; it was a proper, traditional namaskara. The narrator wished him luck in his marriage and then left.

That afternoon, when I was resting, Ranga came to my house with a couple of oranges in his hand. A generous, considerate fellow. It would be a fine thing to have him marry, settle down and be of service to society, I thought. For a while we talked about this and that. Then I came to the point. “Rangappa, when do you plan to get married?” “I am not going to get married now,” he said. “Why not?” “I need to find the right girl. I know an officer who got married only six months ago. He is about thirty and his wife is twenty-five, I am told. They will be able to talk lovingly to each other. Let’s say I married a very young girl. She may take my words spoken in love as words spoken in anger. Recently, a troupe in Bangalore staged the play Shakuntala. There is no question of Dushyantha falling in love with Shakuntala if she were young, like the present-day brides, is there? What would have happened to Kalidasa’s play? If one gets married, it should be to a girl who is mature. Otherwise, one should remain a bachelor. That’s why I am not marrying now.”

- Considerate- thoughtful, concerned

- Troupe- a group of dancers, actors or other entertainers who tour to different venues

Ranga paid the author a visit that afternoon with a few oranges, which the narrator thought was very thoughtful of him. Given how nice Ranga is, the author thought it would be a good deed to marry him to a girl who is equally nice. They talked for a while, and then the narrator asked Ranga about his feelings about marriage. Ranga expresses that he does not intend to marry right away because he wants to find the right girl. He gives the example of a thirty-year-old officer who married a twenty-five-year-old woman. Because they are both adults, they will understand each other's actions and behaviour. Whereas if the narrator meets a very young girl, she may misinterpret his words or actions because she is not mature enough. He even mentions the Mahabharata love storey of Shakuntala and Dushyantha, and how he would not have fallen in love with Shakuntala if she had been too young. In that case, Kalidasa's play would not have existed. That is why he intends to remain single until he meets the right girl.

“Is there any other reason?” “A man should marry a girl he admires. What we have now are arranged marriages. How can one admire a girl with milk stains on one side of her face and wetness on the other, or so young that she doesn’t even know how to bite her fingers?” “One a neem fruit, the other, a bittergourd.” “Exactly!” Ranga said, laughing. I was distressed that the boy who I thought would make a good husband, had decided to remain a bachelor. After chatting for a little longer, Ranga left. I made up my mind right then, that I would get him married.

Rama Rao’s niece, a pretty girl of eleven, had come to stay with him. She was from a big town, so she knew how to play the veena and the harmonium. She also had a sweet voice. Both her parents had died, and her uncle had brought her home. Ranga was just the boy for her, and she, the most suitable bride for him.

The narrator introduces us to Ratna, a new character in the storey. Rama Rao's niece, she is eleven years old. She had lost both of her parents, so her uncle brought her from the big city to his house. She had a beautiful voice and could also play the harmonium and veena. Ranga and Ratna, according to the narrator, would make a perfect couple.

Since I was a frequent visitor to Rama Rao’s place, the girl was quite free with me. I completely forgot to mention her name! Ratna, it was. The very next morning I went to their house and told Rama Rao’s wife, “I’ll send some buttermilk for you. Ask Ratna to fetch it.” Ratna came. It was a Friday, so she was wearing a grand saree. I told her to sit in my room and requested her to sing a song. I sent for Ranga. While she was singing the song— Krishnamurthy, in front of my eyes — Ranga reached the door. He stopped at the threshold. He did not want the singing to stop, but was curious to see the singer. Carefully, he peeped in. The light coming into the room was blocked. Ratna looked up and seeing a stranger there, abruptly stopped

- Threshold- a strip of wood or stone forming the bottom of a doorway and crossed in entering a house or a room

Ratna was quite familiar with the narrator because he frequently visited Rama's place. The narrator devised a strategy to introduce Ratna to Ranga. He asked Rama to send Ratna to his house because he needed to send them some buttermilk. She came fully dressed. The narrator insisted on her singing a song while he sent someone to call Ranga. Ranga arrived at the door just as she was finishing her song. Her melancholy voice touched his ears, and he didn't want to disrupt her singing, so he stood at the door. He was curious to see the singer and tried to look very carefully, which disrupted the lighting in the room. Ratna immediately stopped singing when she noticed a stranger.

Suppose you buy the best quality mango. You eat it slowly, savouring its peel, before biting into the juicy flesh. You do not want to waste any part of it. Before you take another bite, the fruit slips out of your hand and falls to the ground. How do you feel? Ranga’s face showed the same disappointment when the singing stopped. “You sent for me?” he asked as he came in and sat on a chair. Ratna stood at a distance, her head lowered. Ranga repeatedly glanced at her. Once, our eyes met, and he looked very embarrassed. No one spoke for a long while.

Ranga's situation is compared by the narrator to dropping a high-quality mango on the floor just before having to enjoy it fully. It was as if something wonderful had been stolen before it could be fully appreciated. Ranga asked the narrator as to why he had summoned him. Ratna was shy, so she looked down, while Ranga stolethily glanced at her. In the room, there was an awkward silence.

“It was my coming in that stopped the singing. Let me leave.” Words, mere words! The fellow said he would leave but did not make a move. How can one expect words to match actions in these days of Kaliyuga? Ratna ran inside, overcome by shyness

After things became awkward, Ranga stated that he believes his presence is what stopped the singing and that he must leave. He, however, did not. He is mocked by the narrator because he had no intention of going. He makes a joke about it, saying that in the Kalyuga, one cannot expect actions and words to match.

After a while, Ranga asked, “Who is that girl, swami?” “Who’s that inside?” the lion wanted to know. The he-goat who had taken shelter in the temple replied, “Does it matter who I am? I am a poor animal who has already eaten nine lions. I have vowed to eat one more. Tell me, are you male or female?” The lion fled the place in fear, it seems. Like the he-goat, I said, “What does it matter to either of us who she is? I’m already married and you aren’t the marrying kind.”

Ranga finally asked the narrator about the girl after a few minutes of awkward silence. The narrator now compares the situation to the well-known storey of the he-goat and the lion, in which he is the he-goat and Ranga is the lion. The narrator responds cleverly and anticipates Ranga's desire to learn more about Ratna. As a result, he says that who she is unimportant because he is already married and Ranga has no plans to marry anytime soon.

Very hopefully, he asked, “She isn’t married, then?” His voice did not betray his excitement but I knew it was there. “She was married a year ago.” His face shrivelled like a roasted brinjal. After a while, Ranga left, saying, “I must go, I have work at home.” I went to our Shastri the next morning and told him, “Keep everything ready to read the stars. I’ll come later.” I tutored him in all that I wanted him to say. I found no change in Ranga when I met him that afternoon. “What’s the matter? You seem to be lost in thought,” I said. “Nothing, nothing’s wrong, believe me.” “Headache? Come, let’s go and see a doctor.”

- Betray- portray (here)

- Shrivelled- shrunken and wrinkled; especially as a result of loss of moisture

- Tutored- taught

Ranga became excited when he heard the narrator's response, though he didn't show it. He asks, full of hope, if she isn't married yet, to which the narrator responds that she is, and probably was a year ago. Ranga was dissatisfied and discouraged. It was obvious that it was all over his face. He left, quoting some work. After staging certain feelings in Ranga's mind for Ratna, our narrator went on to finish his play. He went to Shastri's village and told him everything that needed to be said and done. Then he saw Ranga that afternoon, and he had the same look of disappointment on his face. When asked if he has a headache, the narrator advises him to see a doctor.

“I have no headache. I’m my usual self.” “I went through the same thing when the process of choosing a girl for me was going on. But I don’t think that that could be a reason for your present condition.” Ranga stared at me. “Come, let’s go and see Shastri,” I suggested. “We will find out whether Guru and Shani are favourable for you or not.” Ranga accompanied me without any protest. As soon as Shastri saw me, he exclaimed, “What a surprise, Shyama! Haven’t seen you for a long time.”

Ranga insists that everything is fine and that he is back to his normal self. The narrator, very wittyly, mentions that he had similar feelings when he was seeing girls for himself, and immediately mentions that this could not be the reason for Ranga. He also suggested that they go see Shastri to see if the stars (Guru for Jupiter and Shani for Saturn) are aligned in their favour. Ranga accompanied him. When he saw Shastri ji, he implied that he hadn't seen the narrator in a long time, which is obviously not true because they had met the day before, the same morning.

Shyama is none other than your servant, the narrator of this tale. I got angry and shouted, “What? Only this morning…” Shastri completed my sentence, “You finished all your work and are now free to visit me.” Had he not done so, I would have ruined our plan by bursting like grains that are kept in the sun to dry. I was extremely careful of what I said afterwards. Shastri turned to Ranga. “When did the young son of our accountant clerk come home? What can I do for him? It’s very rarely that he visits us.”

The narrator reveals his pet name, Shyama, as he was known in the village. Because they saw each other that morning, the narrator assumed Shastri was lying and responded immediately. Shastri, on the other hand, finished his sentence and saved the entire situation. Shyama realised what he was about to do and began to take extra precautions. Shastri continued his performance and pretended to be surprised when he saw Ranga.

“Take out your paraphernalia. Our Rangappa seems to have something on his mind. Can you tell us what’s worrying him? Shall we put your science of astrology to the test?” There was authority in my voice as I spoke to Shastri. He took out two sheets of paper, some cowries and a book of palmyra leaves, saying, “Ours is an ancient science, ayya. There’s a story to it… But I won’t tell you that story now. This is not a harikatha which allows you to tell a story within a story… You may get bored. I’ll tell it to you some other time.”

- Paraphernalia- trappings associated with a particular institution or activity that are regarded as superfluous

- Cowries- a marine mollusc which has a glossy, brightly patterned domed shell with a long, narrow opening

- Palmyra- palm tree

- Harikatha- Story of Lord

With full authority, the narrator asks that the Shastri bring out all of his tools to assist in resolving whatever is going on in Ranga's mind. Shastri took out his essentials and told them that this is all ancient science, but he won't recite it now because it would bore them both, but he does intend to tell it later.

Shastri moved his lips fast as he counted on his fingers and then asked, “What’s your star?” Ranga didn’t know. “Never mind,” Shastri indicated with a shake of his head. He did some more calculations before saying in a serious tone, “It’s about a girl.” I had been controlling my laughter all this while. But now I burst out laughing. I turned to Ranga. “Exactly what I had said.” “Who is the girl?” It was your humble servant who asked the question.

Shastri moved his lips quickly while counting and asked Ranga about his star, which he didn't know about. Shastri suggested that it is manageable. He appeared to be performing some calculations. After a brief moment, he indicated that Ranga is thinking about a girl. Shyama couldn't stop laughing despite his best efforts. As a result, he posed the question to Shastri, inquiring about the girl's details.

Shastri thought for a while before replying, “She probably has the name of something found in the ocean.” “Kamala?” “Maybe.”

“Could it be Pachchi, moss?” “Must it be moss if it’s not Kamala? Why not pearl or ratna, the precious stone?” “Ratna? The girl in Rama Rao’s house is Ratna. Tell me, is there any chance of our negotiations bearing fruit?” “Definitely,” he said, after thinking for some time. There was a surprise on Ranga’s face. And some happiness. I noticed it. “But that girl is married…” I said, Then I turned to him. His face had fallen

Shastri thought for a moment before responding that the girl's name is most likely derived from something found in the ocean. They guessed Kamala, Pachchi, moss, pearl, and then Shastri said Ratna. Everything came together now for a girl named Ratna, Rama Rao's niece. Ranga was completely preoccupied with her. Ranga was both surprised and relieved that Shastri's predictions had come true. When he realised she was married, he was immediately disappointed.

“I don’t know all that. There may be some other girl who is suitable. I only told you what our shastra indicated,” Shastri said. We left the place. On the way, we passed by Rama Rao’s house. Ratna was standing at the door. I went in alone and came out a minute later.

Shastri stated that he did not know everything and that there could be another suitable girl. To make it appear genuine, Shastri interjected in their name guessing game and informed them that he only told them what could be read. They both left and crossed Rama Rao's door, where Shyama went to see Ratna for a minute and then returned.

“Surprising. This girl isn’t married, it seems. Someone told me the other day that she was. What Shastri told us has turned out to be true after all! But Rangappa, I can’t believe that you have been thinking of her. Swear on the name of Madhavacharya and tell me, is it true what Shastri said?”

I do not know whether anyone else would have been direct. Ranga admitted, “There’s greater truth in that shastra than we imagine. What he said is absolutely true.”

- Madhavacharya- an exponent of Vedantic philosophy from South India

When the narrator returns, he announces that, fortunately, Ratna is not married, and that someone may have misinformed him about this. The narrator expresses surprise that he has been thinking about Ratna and asks him to swear on the truth. Ranga surprised him by telling him that everything Shastri said was true. His faith in all the Shastras had grown stronger.

Shastri was at the well when I went there that evening. I said, “So Shastrigale, you repeated everything I had taught you without giving rise to any suspicion. What a marvellous shastra yours is!” He didn’t like it at all. “What are you saying? What you said to me was what I could have found out myself from the shastras. Don’t forget, I developed on the hints you had given me.” Tell me, is this what a decent man says?

- Marvellous- causing great wonder; extraordinary

Shyama went to see Shastri that evening while he was near the well and complimented him on how well he followed Shyama's instructions. Shastri didn't seem to agree with what the narrator was saying. As a result, he says that everything he said can be found in the Shastras. He was disagreed that the entire conversation had been staged.

Rangappa had come the other day to invite me for dinner. “What’s the occasion?” I asked. “It’s Shyama’s birthday. He is three.” “It’s not a nice name —Shyama,” I said. “I’m like a dark piece of oil-cake. Why did you have to give that golden child of yours such a name? What a childish couple you are, Ratna and you! I know, I know, it is the English custom of naming the child after someone you like… Your wife is eight months pregnant now. Who’s there to help your mother to cook?” “My sister has come with her.” I went there for dinner. Shyama rushed to me when I walked in and put his arms round my legs. I kissed him on his cheek and placed a ring on his tiny little finger.

The narrator now jumps ahead a few years, to a time when Ranga and Ratna are happily married, have a three-year-old son, and Ratna is eight months pregnant. Ranga's sister had arrived to assist them. Shyama's birthday had arrived! Yes, the couple named their son after the narrator, as it is a common foreign custom to name your child after someone you genuinely admire. When the narrator arrived for dinner, Shyama ran up to him, only to show his affection by holding his leg. The narrator kissed him and presented him with a ring.

Allow me to take leave of you, reader. I am always here, ready to serve you. You were not bored, I hope?

The narrator sends a final note to all of the readers, hoping they were not bored.

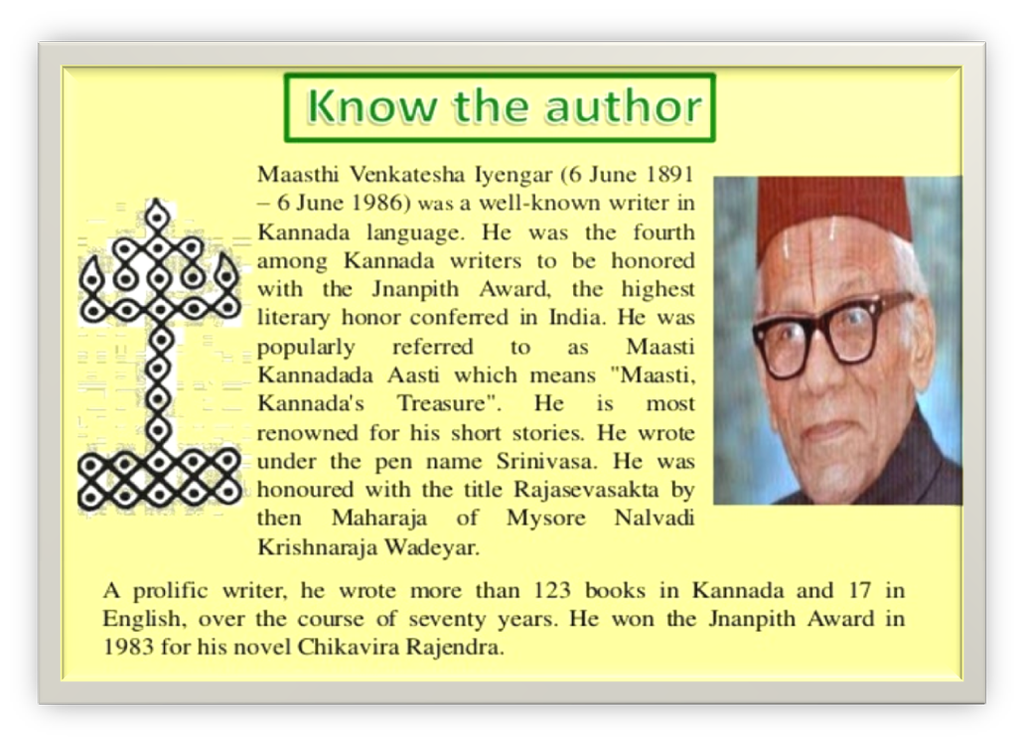

About the Author

Masti Venkatesha Iyengar (June 6, 1891 – June 6, 1986) was a well-known Kannada writer. He was the fourth Kannada writer to be honoured with the Jnanpith Award, India's highest literary honour. He was popularly known as Maasti Kannadada Aasti, which translates as "Maasti, Kannada's Treasure." His short stories are his most well-known works. Srinivasa was the pen name he used when writing. The title Rajasevasakta was bestowed upon him by the then Maharaja of Mysore, Nalvadi Krishnaraja Wadeyar.

PathSet Publications

PathSet Publications

ACERISE INDIA

ACERISE INDIA